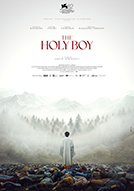

The Holy Boy

| Original title: | The Holy Boy |

| Director: | Paolo Strippoli |

| Release: | Vod |

| Running time: | 122 minutes |

| Release date: | Not communicated |

| Rating: |

Mulder's Review

From the very first minutes, Paolo Strippoli's The Holy Boy promises to be a much more disturbing film than a classic supernatural thriller, revealing a story where grief, faith, and moral decadence creep discreetly beneath an almost serenely smiling facade. Set in the isolated alpine village of Remis, proudly nicknamed the “Valley of Smiles,” the film uses this forced happiness until it becomes something strange, a collective performance masking wounds too deep to be faced in the light of day. Into this strange utopia arrives Michele Riondino as Sergio Rossetti, a once-famous judo champion now reduced to being an emotionally exhausted substitute teacher, a man trying to outrun grief as if sorrow were a physical opponent he could outpace. His abrasive cynicism contrasts delightfully with the unsettling cheerfulness of the town, and his arrival becomes the prism through which we discover the village's true secret: its omnipresent happiness is not a state of healing, but an addiction made possible by a miracle that no one wants to question.

This miracle has a face, that of Giulio Feltri, whose portrayal of Matteo is the emotional core of the film and one of its most discreetly moving achievements. Matteo is adored, mythologized, programmed as a sacred device by his father Paolo Pierobon, and presented by the clergy, such as Don Attilo, as a being halfway between an angel and a commodity; his embrace has the power to ease pain without erasing memory. It is a miracle tailor-made for a town traumatized by a past train disaster and eager to erase the consequences of the emotion. What makes The Holy Boy so captivating is that Paolo Strippoli refuses to romanticize Matteo. He is not just a sacred figure, but a lonely, queer teenager, crushed by a responsibility he never chose, harboring darker desires, confusions, and abilities that make this gift deeply ambiguous. When Sergio meets him, what begins as gratitude slowly transforms into a surrogate father-son bond, one of the film's most human achievements: two outsiders finding in each other what Remis denied them, namely an authentic emotional connection rather than numbing comfort.

Visually, The Holy Boy feeds on the tension between pastoral beauty and suffocating terror, with cinematography by Cristiano Di Nicola and evocative design creating a place that is both real and spiritually sick. The heavy wooden interiors, the disturbing common rooms, and the abandoned train station, left to decay like a wound the city refuses to clean, become symbolic spaces where trauma has not disappeared, but has simply been buried under ritualized denial. What struck us most, especially recalling the murmurs during festival screenings where audiences would sit in stunned silence after the end, is that the film's horror does not come from jump scares or gory scenes, but from the gradual realization that the village willingly sacrificed humanity to achieve relief. This is a folk horror film that does not rely on ancient curses, but on something disturbing and modern: a culture so terrified of pain that it prefers emotional externalization to emotional resilience.

There is an undeniable audacity in the way Paolo Strippoli superimposes elements of the genre (echoes of The Wicker Man, shades of Carrie, nods to Let the Right One In) while shaping them into something of his own, avoiding the easy cliché of traumatic horror and instead questioning what happens when a community glorifies the erasure of suffering. Romana Maggiora Vergano brings down-to-earth warmth to the role of Michela, the barmaid who is the first to initiate Sergio into Remis' secret, while Michele Riondino's performance grows richer as Sergio relearns how to live thanks to his bond with Matteo. Meanwhile, Giulio Feltri anchors the film's descent into moral darkness with a heartbreaking, unsettling, and deeply human performance, particularly as Matteo begins to explore aspects of his power that raise frightening questions about consent, dependence, and the price of adoration. When the film finally reaches its feverish climax, the spectacle never drowns out its soul; behind every chaotic image lies a haunting meditation on pain as something necessary, even sacred, because it reminds us that we are alive.

As the credits roll, The Holy Boy lingers like a wound, not only because it horrifies, but also because it dares to suggest that true monstrosity lies not in supernatural forces, but in our desperation to feel nothing at all. Paolo Strippoli creates a biting and melancholic parable about the dangers of worshipping salvation at any cost, about communities willing to sanctify emotional amputation rather than face grief head-on, and about the tragic fate of a boy turned into a vessel instead of being allowed to remain a child. It's a frightening, beautifully performed, morally complex film that continues to provoke long after the final image has faded, a story that asks whether relief without growth is worth the price of our humanity. For its haunting ideas, its gripping performances, and the emotional honesty that lies beneath its genre bravado, I would give The Holy Boy a high rating.

The Holy Boy

Directed by Paolo Strippoli

Written by Jacopo Del Giudice, Paolo Strippoli, Milo Tissone

Produced by Laura Paolucci, Ines Vasiljević, Stefano Sardo, Domenico Procacci, Jožko Rutar, Miha Černec

Starring Michele Riondino, Giulio Feltri, Paolo Pierobon, Romana Maggiora Vergano

Cinematography: Cristiano Di Nicola

Edited by Federico Palmerini

Music by Federico Bisozzi, Davide Tomat

Production companies: Fandango, Nightswim, Spok Films, Vision Distribution

Distributed by Vision Distribution (United States)

Release dates: August 30, 2025 (Venice), September 17, 2025 (Italy)

Running time: 122 minutes

Seen on December 13, 2025 at Max Linder Panorama

Mulder's Mark: