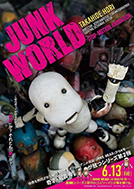

Junk world

| Original title: | Junk world |

| Director: | Takahide Hori |

| Release: | Vod |

| Running time: | 104 minutes |

| Release date: | Not communicated |

| Rating: |

Mulder's Review

If Junk Head, directed and written by Takahide Hori, gave the impression of discovering a cursed VHS tape from another dimension, then Junk World is the moment when we realize that the person who made this tape also built, by hand, with six people and without any fear of going too far, the entire underground city in which it was filmed. Watching it at the PIFFF festival, you experience that rare sensation of being both delighted and slightly assaulted: the screen is filled with grotesque little characters rushing to the edges of the frame, biomechanical monsters that seem straight out of a feverish nightmare by H. R. Giger, and proudly childish gags that only a filmmaker totally confident in his own strangeness can get away with. And then the credits roll with behind-the-scenes footage that not only showcases the craftsmanship, but reframes the whole experience as a minor miracle of workmanship. You can almost feel the fingerprints on the universe. Even when the film is messy, you keep watching it as you would watch an elaborate model train set that is also, for no reason, deeply perverse.

The setting is deceptively classic for a science fiction film, until it isn't. Centuries after a truce between humans and Mulligan clones (a workforce designed to obey, then forced into hiding, then into violent rebellion), a joint expedition is organized to investigate a mysterious anomaly that presents itself as a wound at the edge of reality. The human side is represented by Lady Torys, played by Atsuko Miyake, a military leader whose authority is evident in both her words and her attire (armor, posture, and a hat that hides as much as it reveals her emotions), while her robot guardian Robin (voiced by Kusako Matsuoka) becomes the beating heart and surprisingly tender soul of the film. The Mulligans send Dante, played by Takahide Hori, a clone soldier whose designed deficiency (the absence of eyes, a genetic choice intended to reinforce his submission) ultimately makes him paradoxically more human than some of the humans in the play, especially when his visor becomes a kind of identity rather than a limitation. The “diplomatic” presence of Ambassador Morse, also voiced by Takahide Hori, is particularly pathetic: bureaucratic incompetence as a recurring punchline, the kind of official who treats survival as if it were unworthy of his position. And then, almost immediately, the mission is hijacked by a radical faction of Mulligan, the Gyura cult, whose coded S&M iconography is not just provocation; it is an ideology transposed into the wardrobe, a tribe that displays its power through modified flesh, fetishized rituals, and the promise of violence as sacrament.

What Junk World does best, almost unfairly well, is to immerse you in a density of invention that would already be impressive in live action, and then remind you that this is a stop-motion film. The action isn't just movement, it's choreography: hand-to-hand combat, mechanical mayhem, weapons that look like toys designed by a very talented and very disturbed child, and sets staged with the clarity of someone who has previewed every movement, because stop-motion retakes are fundamentally painful. The creature design is a constant assault of creativity, from parasites that are mercilessly crushed to monsters that resemble ecosystems with teeth. Even the humor is rooted in the physical world: scatological jokes, musical interludes, censored visual gags that deliberately “miss,” and, of course, the famous phallic “mushrooms” that propel the film into that specific festival-friendly zone, where the audience laughs partly because it's funny and partly because they can't believe the film dared to do that. This is also where the artisanal aesthetic comes into its own: even with shinier surfaces than in Junk Head (the past is literally more polished), the film insists on its tactile reality, as if it wants you to admire the craftsmanship, then immediately use it as a weapon against your comfort.

Narratively, Takahide Hori pursues an ambitious goal: time travel and dimensional rupture as a circular structure that reveals itself in pieces, each act (or chapter) reframing what you thought you understood. When the film works, it is surprisingly readable for something so crazy, less confusing than relentless, as if you were being dragged at full speed through a maze while someone kept giving you new maps that contradicted the old ones. The anomaly is not just an element of the plot; it's a machine of paradoxes, temporal ramifications, and alternative perspectives on the same event. The trick is that the film often suggests loops rather than drowning you in them; it lets you deduce, then keeps the emotional threads (Torys's rigidity, Dante's reluctant empathy, Robin's evolution) like a rope for you to cling to. There's even a metatextual nod to the complexity: the characters are about to explain the science, but the film doesn't pay attention to it, because what matters isn't the math, but the momentum and the feeling of being trapped in a story that folds in on itself.

And yet, this is where Junk World becomes a film, yes, but rather than an unreserved triumph: the same appetite for world-building that makes it intoxicating also threatens to suffocate it. The film is overflowing with traditions, factions, hierarchies, political history, religious allegories, and grotesque anthropology; it keeps expanding, sometimes as if afraid that if it stopped, the spell would be broken. This can leave the characters stuck in their roles rather than their personalities, and moments that should elicit emotion come across as half-baked, as the film rushes on to the next revelation or insane visual. This is the classic problem of a filmmaker who has too many great ideas and a universe too vast to contain them: the audience is constantly impressed, sometimes moved, and sometimes left behind. You don't really follow the plot, you survive it, and the film's best narrative trick, recontextualization, doesn't always manage to compensate for the feeling that you're watching a brilliant trailer for a clearer, more focused epic film.

Yet one cannot help but emphasize how unique this experience is, especially in a movie theater where the collective reaction is an integral part of the film's rhythm: the grunts, the laughs, the whispers of “what the hell is that?”, the sudden silence when the craftsmanship reaches a new level. Junk World is one of those films where even the flaws seem connected to its identity; the overloaded mythology and sometimes slow pace are, strangely enough, the price to pay for something that refuses to be normal. It is a film made by an auteur in the most literal sense of the word: no committee came along to smooth out the rough edges, no studio came along to erase the fetishism, the grime, the melancholy, or the inexplicable fantasy. And when the end credits point to the nightmare that Junk Head fans already know is inevitable, the story ends on a bittersweet note: this world still has air, space, and a kind of fragile possibility, but the story is already leaning toward decadence. This inevitability gives the madness a slight tragic shadow and makes Robin's “origin” the most discreet punch in a film full of loud punches. Junk World is a stunning, often hilarious, sometimes disgusting stop-motion odyssey whose imagination and craftsmanship border on the miraculous, even if its narrative ambition sometimes collapses under the weight of its irresistible and unruly universe.

Junk World

Written and directed by Takahide Hori

Starring Atsuko Miyake

Cinematography: Takahide Hori

Edited by Takahide Hori

Production companies: Yamiken

Running time: 104 minutes

Seen on December 13, 2025 at Max Linder Panorama

Mulder's Mark: