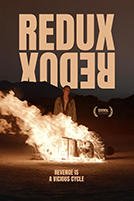

Redux, Redux

| Original title: | Redux, Redux |

| Director: | Kevin McManus, Matthew McManus |

| Release: | Cinema |

| Running time: | 109 minutes |

| Release date: | 20 february 2026 (France) |

| Rating: |

Mulder's Review

Redux Redux hits like a punch in the gut, uncompromising from the very first seconds, opening with an image so raw that it seems straight out of a nightmare: Irene Kelly, played by Michaela McManus, watches as flames consume a man tied to a chair, long before the film reveals the endless and terrible routine that this represents. What emerges from this dazzling introduction is not the expected exercise in multiverse spectacle, but something far stranger and more intimate: an odyssey of vengeance that unfolds across countless dimensions while remaining anchored in the eroded soul of one woman. Writer-directors Kevin McManus and Matthew McManus, returning after their quietly devastating film The Block Island Sound, use the sci-fi premise only as a scaffolding; the building itself is a study of grief calcifying into ritual, ritual turning into addiction, and addiction draining its host until she becomes a shadow stalking a ghost. Irene isn't stalking a man, she's pursuing the fantasy of undoing the unthinkable, and the McManus brothers anchor that truth in every mechanical, joyless iteration of her vengeance.

What sets Redux Redux apart from the recent glut of multiverse fiction is its absolute refusal to embellish the concept. While Hollywood blockbusters immerse viewers in universes shaped by eccentricities and gadgets, the McManus brothers instead insist on familiarity: the same roadside restaurants, the same beige motel rooms, the same fluorescent-lit supermarket aisles, repeated with slight variations that serve only to unsettle Irene's routine. This banality of infinity is the film's stroke of genius. These worlds do not seem like possibilities, but rather traps. Irene's meticulous system, with its sets of keys, escape routes, and carefully timed executions, feels less like the work of a time-traveling killer and more like the obsessive itinerary of someone long imprisoned by their own grief. An anecdote that the film slips in discreetly—a recurring, awkwardly tender night spent with Jonathan, played with characteristic wild charm by Jim Cummings—reveals how Irene tries, unsuccessfully, to mimic human relationships in each new world. It's a routine comfort, the equivalent of the loneliness one feels when eating the same reheated leftovers across universes. That's where the sad joke lies: the multiverse doesn't expand her life. It reduces it to a loop.

That loop finally breaks when Irene meets Mia, played with raw, volatile electricity by Stella Marcus, who almost steals the show from the film's seasoned star. Their first encounter (Mia still bound in a bathtub, Neville's shadow looming somewhere in the house) reorients the narrative's trajectory. Irene has saved many girls by eliminating Neville (Jeremy Holm, fierce even in silence), but she has never intervened early enough to meet one alive. Mia is neither a symbol nor a sidekick; she is a mirror that shows Irene what years of vengeance have done to her. The film's most astute anecdote lies in the way Mia studies Irene's every move as if to absorb it, imitating her abrupt confidence, her sudden flashes of tactical clarity, and even her self-destructive bravado. Their dynamic evokes the best “accidental family” duos in genre cinema, but with a harder, more wounded edge—Terminator 2 refracted through a lo-fi indie prism, where Sarah and John Connor have already lived through several traumatic lives before meeting.

The film does not develop outwardly, toward spectacle, but inwardly, toward the construction of a world based on human fragility. A fascinating detour inside a dilapidated bunker, where black market dealers from the multiverse try to convince Irene to give up her machine, becomes one of the film's most memorable sequences, not for the action, but for its implications. In this universe, these travelers are common enough that exotic technology resembles an auto part sold under the table. This banality reinforces the film's overall thesis: infinite worlds do not bring infinite freedom; they only multiply the places where pain can fester. Even when Irene glimpses a universe where her daughter has become a teenager—alive, thriving, loved—it is not a revelation of hope, but of torment. She cannot enter this girl's life without destroying her, and the multiverse, despite its cosmic scope, still cannot heal the wound that defines her. It is here, in these silent devastations, that Michaela McManus delivers her most haunting performance, her shoulders perpetually tense between assassin and mother, her eyes sparkling with the pain of someone who has forgotten what it is like to live without rage.

The genius of Redux Redux lies in the fact that it never moralizes its themes, even when it tackles them head-on. Stories of revenge often hinge on a single murder, the cathartic moment that restores balance. Here, it is the repetition itself that is the villain. Killing Neville hundreds of times does not dilute his evil, but dilutes Irene's humanity. In a particularly striking image, Irene slips into the multiverse machine—a steel coffin glowing with hellish red—in search of an escape, but finding only a metaphor for the grave she digs again in each dimension. The film's emotional momentum builds through the back-and-forth between Irene and Mia: Irene trying to prevent the girl from inheriting her monstrosity, Mia trying to prove she is strong enough to bear it. Their arguments are marked by recognizable adolescent-parental tensions, but also by existential stakes: each disagreement risks not only emotional repercussions, but cosmic consequences. The McManus brothers, wisely and consistently, keep the camera close to their faces, letting tiny fractures of vulnerability signal the tectonic shifts occurring internally.

As the climax unfolds, Jeremy Holm finally has the space to embody all of Neville's sadism, and it's terrifying. Jeremy Holm achieves the rare feat of making the film's most familiar image—the killer meeting his end—seem newly monstrous simply through subtle changes to his physique and presence. Yet even here, the film resists easy dichotomies. Irene's struggle is not against Neville, but against herself, and the multiverse, in all its infinite expanse, becomes the stage on which she slowly recognizes the futility of trying to resurrect a past that no longer belongs to her. If the finale relies on genre-specific carnage, it is for the purpose of closing a wound rather than opening another. The emotional reward is not achieved through spectacle, but through the difficult decision to live toward the future rather than the past, a choice Irene is ultimately able to make because Mia forces her to confront what she has become.

Redux Redux stands out not because it reinvents the multiverse, but because it rejects the self-indulgence of the genre. The film understands that grief is already a multiverse: every memory imagined in a thousand variations, every alternative outcome that haunts the mind. By giving Irene the literal ability to pursue these “what ifs,” the McManus brothers create a rare sci-fi thriller that functions both as muscular entertainment and a philosophical lament. It's a film constructed from modest tools—a dented metal box, dusty diners, gas station parking lots—but elevated by meticulous craftsmanship, textured performances, and a willingness to recognize that the most devastating battles are never fought across time and space, but within the human heart.

Redux Redux

Written and directed by Kevin McManus, Matthew McManus

Produced by Michael J. McGarry, Kevin McManus, Matthew McManus, Nate Cormier, PJ McCabe

Starring Michaela McManus, Jim Cummings, Jeremy Holm, Taylor Misiak, Grace Van Dien, Stella Marcus, Minita Gandhi, Michael Manuel

Cinematography: Alan Gwizdowski

Edited by Derek Desmond, Nate Cormier

Music by Paul Koch

Production company: Mothership Motion Pictures

Distributed by Saban Films

Release dates: March 8, 2025 (SXSW), February 20, 2026 (United States)

Running time: 109 minutes

Seen on December 11, 2025 at Max Linder Panorama

Mulder's Mark: