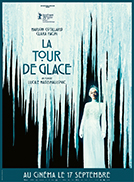

The Ice Tower

| Original title: | La tour de glace |

| Director: | Lucile Hadžihalilović |

| Release: | Vod |

| Running time: | 118 minutes |

| Release date: | Not communicated |

| Rating: |

Mulder's Review

Set in a foggy France of the 1970s, where memory merges with myth, The Ice Tower brings together a series of powerful images and ideas, but rarely moves the viewer. It is an elegant snow globe that is more admired than felt.

Lucile Hadžihalilović draws inspiration from Hans Christian Andersen's The Snow Queen to tell the story of a young runaway's initiation into the seductions and dangers of cinema. On paper, this fits perfectly with the director's sensibility: a world of rituals, mirrors, and thresholds where identity is a costume that transforms you. Newcomer Clara Pacini plays Jeanne, the eldest child in a foster home who clutches her late mother's pearl necklace like a talisman and slips, almost by accident, into a movie studio where The Snow Queen is being filmed. The script promises an explosive mix of behind-the-scenes intrigue and fairy-tale dangers, but what follows often feels more like a museum installation—immaculate, glacial, and immune to temperature fluctuations—than a living drama.

There are flashes of life. An anecdote at the beginning of the film becomes a Rosetta Stone: Jeanne, fascinated by a painted horizon on the set, keeps walking until she bumps her forehead against the scenery with a dull, funny thud. It's an honest little bruise and a perfect blueprint for the film's theme: how desire confuses image and path. Through a crack in the wall, Jeanne spies on the star of the production, Cristina, played by Marion Cotillard with austere glamour and watchful thirst; later, she hides in Cristina's wardrobe to listen to the warmer, more disordered human tones that escape between takes. The orbit around Cristina is sketched lightly but precisely: Max, a driver/“doctor” embodied with gentle menace by August Diehl, who can restart the engine with a syringe; a director named Dino, played with self-caricaturing wink by Gaspar Noé; and a capricious raven whose tantrums on set conveniently reshuffle the cast. Every detail hints at a film ready to break its own spell. Yet these gestures rarely accumulate to create momentum; the pace remains static, as if the film fears that emotion will cloud the glass.

Technically, the work is formidable, and at times so perfect that it becomes its own obstacle. In collaboration with cinematographer Jonathan Ricquebourg, Lucile Hadžihalilović frames the action through doors and openings to create a faux 1.33:1 in a widescreen, a clever spatial corset that reflects Jeanne's restricted action. The soundtrack consists of sharp friction sounds—the screech of skate blades, the silence of falling snow, the sterile calm of a screening room after the applause—while the production design alternates between real winter and artificial winter until your eye can no longer tell the difference. A prismatic crystal, torn from Cristina's dress, returns as a recurring motif: place it in front of the lens and the world fractures beautifully, conveying the idea that the same light refracts at different times in different hearts. The problem is that the film is convinced that motifs are enough. The images communicate temperature exquisitely, but they rarely convey warmth.

The central duo is the film's greatest asset, but also its missed opportunity. Marion Cotillard divides Cristina into three simultaneous beings: the snow queen in front of the camera, the celebrity who monitors her myth in the corridors, and the tired woman who bleeds through her makeup. She does so with a precision that invites the gaze, then punishes it. Clara Pacini responds with a poised and reserved reversal that refuses to over-explain Jeanne; she quickly learns the codes of adulthood but is tender enough to believe that a story can save you if you commit to it. Together, they generate a loaded label—mentorship that could be maternal, attraction that could be aspiration—but the film keeps their dynamic so carefully glazed that its danger rarely reaches the gut. When Cristina whispers promises of eternity at the edge of a cliff, or when she haunts Jeanne after inviting her for a drink, we sense the contours of an edifying narrative; what we don't feel is the unease that should accompany it.

Several influences hover in the attic: Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger's The Red Shoes literally hangs as a poster on the studio wall; we sense slight tremors of All for Eve in the silent reattributions of power; we even glimpse a hint of gothic behind the scenes when the raven torpedoes a rival extra. The screenplay by Lucile Hadžihalilović and Geoff Cox, whose thematic echoes others attribute to Alanté Kavaïté, opts for fabulous minimalism and negative space, which can be a bold choice; here, it often gives the impression of a lack of substance. The film's fragments of voiceover, recited like bedtime stories by Aurélia Petit, connect the mountain panoramas to the studio caves with icy poetry, but they also serve as a crutch, providing a mythical framework where the drama struggles to provide one. By the time the narrative takes its most disturbing turn, the film has already anesthetized us with silence and fog; transgression appears more as a concept than as a wound.

To be fair, the historical setting is not just a facade. By setting the action in the 1970s, before protective measures were put in place, Lucile Hadžihalilović frames intimacy and power with an ethical distance that allows the film to critique the cost of myth-making without preaching. The best sequence condenses this criticism into an indelible stain: red blood dragged across white ice, an image that says “beauty records the impact” more clearly than any dialogue. Elsewhere, a painted snowy landscape acts as a false horizon, and the camera sometimes frames the action as if it were inside a projector, persuading us that every adult myth was once a children's story told after lights out. These are powerful ideas that stick in the mind. What they don't do is enliven the long passages in between, which too often give the impression of watching a beautiful screen rather than being drawn into the action.

The Ice Tower is a reverie about how we learn to separate the horizon from the image and the high price that lesson can cost. We see the film it wants to be: a double exposure of teacher and student, setting and story, danger and desire, ending on a note that withholds catharsis in favor of honest pain. But admiration outweighs involvement. Marion Cotillard delivers an impeccably controlled performance, which understands fame as both a job and a wound; Clara Pacini stands out as a true revelation precisely because she doesn't try too hard; and Lucile Hadžihalilović remains a singular image maker. The images are icy, complex, sometimes sublime. Too often, the heart remains frozen behind the glass.

The Ice Tower

Directed by Lucile Hadžihalilović

Written by Lucile Hadžihalilović, Geoff Cox

Produced by Muriel Merlin, Ingmar Trost

Starring Marion Cotillard, Clara Pacini, August Diehl, Gaspar Noé

Cinematography: Jonathan Ricquebourg[2]

Edited by Nassim Gordji Tehrani

Production companies: 3B Productions, Arte France Cinéma, Sutor Kolonko, Albolina Film

Distributed by Metropolitan Filmexport (France)

Release dates: February 16, 2025 (Berlinale), September 17, 2025 (France)

Running time: 118 minutes

Seen on September 17, 2025 (press screener Fantastic Fest 2025)

Mulder's Mark: