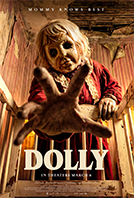

Dolly

| Original title: | Dolly |

| Director: | Rod Blackhurst |

| Release: | Vod |

| Running time: | 82 minutes |

| Release date: | 06 march 2026 |

| Rating: |

Mulder's Review

Dolly announces its intentions from the very first images: a prologue in the form of a nursery rhyme that turns into a threat, followed by a forest scene composed of cracked porcelain faces nailed to the bark like faded warnings that no one has heeded. Director Rod Blackhurst (co-writer with Brandon Weavil) strips the script of all superfluous elements: Macy (Fabianne Therese) travels to the woods of Tennessee with her boyfriend Chase (Seann William Scott) in the hope that he will propose to her in a picturesque setting; but instead they encounter an imposing, almost silent figure wearing a doll's mask, who calls himself Dolly (played by Max the Impaler). In a few brutal and breathless moments, Macy is dragged into a ruined house and resurrected as Dolly's baby, complete with diapers, bottles, crib, and all. It's the kind of plot that seems thin in summary, but it packs a punch, because Blackhurst isn't going for mystery, he's going for sensation: he wants you to feel the sand, hear the footsteps, taste the dried blood in the back of your throat.

Shot in Super 16mm by Justin Derry, the film has an authentically rough patina that goes beyond simple mood lighting; the grain is an integral part of the menace, a creeping texture that makes the walls feel damp and the air heavy. The lineage is clear: Tobe Hooper's The Texas Chain Saw Massacre, the brutality of the 1970s in remote areas, and, in its structure, a dark fairy tale cadence that Blackhurst literalizes by dividing the film into chaptered episodes. This choice, which often serves as a crutch in lesser thrillers, works here like turning the pages of a distorted storybook, each title heralding a new escalation: Mother, House, Reunion. The chapters do not deepen the plot, but rather the ritual, reinforcing the idea that Macy is not only imprisoned, she has been enlisted in someone else's myth.

The house is the film's co-star, a mausoleum of dolls covered in dirt, toys, and mold, where care and punishment merge into a single disturbed choreography. Rod Blackhurst stages sets like endurance tests: force-feeding that shifts from childish to obscene; a vicious spanking that plunges Dolly into a spiral of shame; escape attempts that smash doors, windows, and bodies with alarming force. What prevents the film from descending into melodrama is its obsession with cycles: how violence teaches, how love can be the ugliest mask of control, how a victim can be pushed, little by little, towards complicity or rebellion. When Macy hears herself say at the beginning: You're not like her, you're not a monster, this phrase hangs over every choice she makes in captivity, both a challenge and a lifeline.

Performance is the driving force. Fabianne Therese gives Macy a nervous resilience that can be seen in her micro-decisions: when to let go, when to get fired up, when to use Dolly's need for a child as a weapon. It's a physically demanding role, based on breath, bruises, and a disconcerting determination, and that's what makes the difference between a screaming machine and a survival thriller with character. Opposite her, Max the Impaler embodies a creature full of contradictions: imposing but childish, dependent but sadistic, an echo of Leatherface with a distinctly feminine menace. The mask stifles expression, so everything relies on posture and tempo: the hesitant step that turns into a charge, the cooing of the nanny that collapses into a strangled scream. In limited screen time, Seann William Scott nuances Chase with credible tenderness, and Ethan Suplee (as the second voice in the house) complicates the threatening landscape with a presence that is both pathetic and predatory.

Technically, the film is a plea for restraint. The practical gore is not only competent, it's tactile, with a gag that dislocates the jaw and elicits a full-body grimace, then boldly returns for an encore. The sound design amplifies the impact: bones crack with jarring realism, tissue scrapes like sandpaper on skin, and Nick Bohun's music evokes discomfort rather than instructs it. Above all, the production resists the modern temptation to smooth out the rough edges with digital retouching; the violence feels captured, not composed, and this analog honesty makes the sets dangerous. When the film flirts with dark humor, it's the nasty kind: we laugh because our nerves need an outlet, not because the film is winking at us.

One can make a legitimate criticism of the novelty. The film is deliberately derivative in its form—the journey through the woods, the division into chapters, the ordeal of the last girl—and its mythology is intentionally skeletal. But “Dolly” deserves to be repeated by questioning it. While many retro revivals are content to reproduce the iconography of the 1970s, Rod Blackhurst tackles the psychosexual anxieties of the era and transposes them into a contemporary register: motherhood as performance and power; the role of step-parent as a test that Macy fears she will fail; the way abusers rename cruelty as “attention.” We sense a conversation establishing itself between the imagery and the subtext, and when the film chooses literalism (diapers, pacifiers, bed rails), it is because that literalism is the horror.

The film's few missteps stem from the same purity that gives it its bite. The relentless structure, particularly in the middle sections, risks monotony—trauma, attempt, reversal, repetition—and the chapter titles, while atmospheric, sometimes foreshadow patterns you've already guessed. A handful of visual homages are obvious enough to pull you out of the moment, and the opacity of the mask sometimes limits what Max the Impaler can express. Yet even here, the film compensates with its pacing; it never lingers long enough on any one beat to dull the edge, and when it accelerates, the propulsion is real.

What ultimately remains is the feeling of dirtiness, both in terms of texture and morality. Dolly is unpleasant by nature, but it is not a meaningless provocation. He understands that the aesthetics of exploitation can be a vehicle for ideas about heritage and identity, and he trusts his audience to accept two truths at once: that this is an unpleasant work, and that the goal is precisely to be unpleasant. By the time Macy makes her final savage choice, the film has already laid out the full scope of its thesis on cycles: who ends them, who prolongs them, and what it costs in both cases. It may display its influences, but the wounds it leaves are entirely its own, and they continue to bloom long after the credits roll.

Dolly

Directed by Rod Blackhurst

Written by Rod Blackhurst, Brandon Weavil

Produced by

Starring Fabianne Therese, Russ Tiller, Michalina Scorzelli, Kate Cobb, Ethan Suplee, Seann William Scott, Max the Impaler

Cinematography: Justin Derry

Edited by Justin Oakey

Production companies: Gentile Entertainment Group, Mama Bear Productions, Mama Bear Studios, Monarque Entertainment, Set Point Entertainment, Witchcraft Motion Picture Company

Distributed by NC

Release dates: NC

Running time: 82 minutes

Seen on September 22, 2025 (press screener Fantastic Fest 2025)

Mulder's Mark: