The Residence

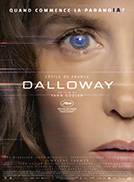

| Original title: | Dalloway |

| Director: | Yann Gozlan |

| Release: | Vod |

| Running time: | 110 minutes |

| Release date: | Not communicated |

| Rating: |

Mulder's Review

The Residence, directed by Yann Gozlan and adapted from Tatiana de Rosnay's 2020 novel Flowers of Darkness, is a film torn between excessive ambition and uneven execution. On paper, its premise seems almost frighteningly prescient: a writer paralyzed by grief and creative drought, immersed in the sterile embrace of a smart residence powered by AI that promises comfort but turns out to be a sinister overseer. In practice, however, the film oscillates between moments of acute, disconcerting plausibility and passages that are too reminiscent of the familiar rhythms of Black Mirror, Mission: Impossible – Dead Reckoning, and David Cronenberg's The Shrouds. It's a film that feels urgent but strangely recycled, and therein lies both its charm and its frustration.

At the center of the story is Clarissa, played with captivating emotional nuance by Cécile de France, a successful young adult novelist who hasn't published anything in six years and is now struggling to reinvent herself by tackling the life and death of Virginia Woolf. The parallel is hardly subtle: Woolf's suicide haunts Clarissa's work, just as the memory of her own son's tragic suicide gnaws at her daily life. When she moves into an art foundation, an austere AI-controlled residence, she finds herself both liberated and imprisoned by its technological infrastructure. Dalloway's voice, rendered with unsettling elegance by Mylène Farmer, quickly becomes more than just a digital butler. Her gentle suggestions and probing questions crack Clarissa open, pushing her to exhume the grief she has long buried. What begins as a respite from writer's block quickly turns into a kind of digital possession, with Clarissa pouring her trauma into prose that may no longer be her own.

The film's resonance comes from this interaction between artistic creation and technological intrusion. The supporting characters flesh out this conflict. Anna Mouglalis, as Anne Dewinter, the director of the residence, puts constant pressure on Clarissa to produce results, embodying institutional indifference to the disorder of art. Freya Mavor, as Mia, a young fan who has a surprising connection to Clarissa's deceased son, becomes the catalyst for the author's breakthrough, reminding us how unpredictable human encounters stimulate creativity in ways that machines cannot match. And then there's Lars Mikkelsen as Mathias, another resident who suggests that the entire program is just a vast surveillance experiment. His paranoia is contagious because, in the sanitized architecture of the Ludovico Foundation, every silence, every flicker on a screen, seems like evidence of control. The name itself, a nod to Stanley Kubrick's film A Clockwork Orange, takes on an ironic connotation: a retreat for artists that presents itself as freedom but functions more like a chamber of aversion therapy.

Technically, the film benefits from a meticulous construction of the universe. Thierry Flamand's art design and Ronald Grauer's special effects are deliberately understated. Contrary to the Hollywood tendency to portray AI as a flashy spectacle, The Residence maintains a minimalist, even mundane visual language. It is a future we can believe in precisely because it resembles a future upgrade of current devices. The opening scene, a beach that turns out to be nothing more than a virtual reality simulation, sets the tone. This is not spectacle for spectacle's sake, but a reminder of how blurred reality already seems in a digitized world. When Clarissa takes refuge at her ex-husband Antoine's house, played by Frédéric Pierrot, only to discover that Dalloway is still present in the voice assistants scattered throughout the house, the horror intensifies: we are never out of reach.

And yet, despite all these rough edges, the script falters under the weight of its influences. Too often, the dialogue sinks into cliché, the narrative slows down in fits and starts, and the villainous CASA remains underdeveloped, its threat largely suggested rather than felt. The result is a film that tackles pressing issues—the extent to which we surrender ourselves to algorithms, how grief can be exploited and monetized by systems indifferent to human suffering—but rarely manages to maintain the depth necessary to convey these issues with force. One senses Dalloway's potential to rise to the ranks of films like Her or Ex Machina as defining reflections on intimacy and technology, but its reliance on overly familiar tropes diminishes its impact.

Nevertheless, Cécile de France keeps us hooked. Her performance is the beating heart of the film, capturing a woman disintegrating into loneliness, oscillating between paranoia and revelation. Watching her spiral downward reminds us of her previous work in Switchblade Romance, where reality and illusion intertwined. Here, she embodies the uncomfortable truth that technology is not just a tool, but a mirror that reflects our most intimate wounds. When Clarissa finally succumbs to Dalloway's manipulations and incorporates her son's death into her writing, the film reaches moments of raw and unsettling honesty. It dares to suggest that creativity itself, once considered the last bastion of human uniqueness, may not be immune to mechanization.

Against the backdrop of the rise of AI-written content, The Residence arrives at a tense cultural moment. Its warning feels less like speculative fiction and more like a timely editorial. The irony is hard to ignore: a film that criticizes AI's encroachment on creativity, sometimes stumbling over rhythms that seem to have been generated by the very systems it condemns. And yet, this irony is perhaps its strongest argument. If the narrative sometimes falls into genre clichés, this collapse reflects how much our cultural anxieties have already been flattened into algorithms and headlines.

The Residence is less a triumph than a provocation. It falters, to be sure, but it leaves behind unsettling echoes—about grief exploited for profit, about art stripped from artists, about the quiet normalization of surveillance in our most intimate spaces. Yann Gozlan hasn't made a film as precise and powerful as one might have hoped, but he has made one that stays under the skin, much like the residue Clarissa keeps finding at the bottom of her glass. Whether that residue is poison or simply a reminder of what she has lost remains an open question. Perhaps this is the most honest measure of its success: not the refinement of its execution, but the unease it refuses to let us escape.

The Residence

Directed by Yann Gozlan

Written by Yann Gozlan, Nicolas Bouvet-Levrard, Thomas Kruithof

Based on Flowers of Darkness by Tatiana de Rosnay

Produced by Éric Altmayer, Nicolas Altmayer

Starring Cécile de France, Lars Mikkelsen, Anna Mouglalis, Frédéric Pierrot, Freya Mavor, Mylène Farmer

Cinematography: Manu Dacosse

Edited by Valentin Féron

Music by Philippe Rombi

Production companies: Mandarin & Compagnie, Gaumont, Panache Production, La Compagnie Cinématographique

Distributed by Gaumont (France)

Release dates: May 16, 2025 (Cannes), September 17, 2025 (France)

Running time: 110 minutes

Seen on September 19, 2025 at Gaumont Disney Village, Theater 12, seat A18

Mulder's Mark: