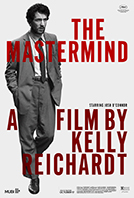

The mastermind

| Original title: | The mastermind |

| Director: | Kelly Reichardt |

| Release: | Cinema |

| Running time: | 110 minutes |

| Release date: | 17 october 2025 |

| Rating: |

Mulder's Review

The Mastermind is the kind of film that sneaks up on you—not because of the heist at its center, but because of how quickly that heist recedes into the background. With her signature restraint, Kelly Reichardt has once again taken a familiar genre and stripped it bare, leaving only the fragments that interest her most: the moments of failure, the silences that sit between bad decisions, and the melancholy absurdity of a man who believes he can outwit the world when he can barely outwit himself. The irony of the title is obvious from the start. The so-called mastermind, James Blaine Mooney, played with bruised, shambling brilliance by Josh O’Connor, is less a criminal genius than a restless dreamer caught in the quicksand of his own mediocrity.

The story, loosely inspired by the 1973 Worcester Art Museum robbery, begins with one of Kelly Reichardt’s most deftly composed openings. On a family trip to a local museum in Massachusetts, James lingers just long enough to slip a figurine into his wife’s handbag while she and their two sons drift away. Nothing explosive happens. There’s no alarm, no chase, no glamour. Just a petty, almost laughable act of theft that tells us everything we need to know about him. He is both invisible and reckless, thrilled by the possibility of getting away with something even as he hides behind the people closest to him. From that moment on, the film circles less around the logistics of a heist and more around the hollow life of a man who insists on calling himself a provider, even as every action he takes pushes his family further toward collapse.

As Kelly Reichardt allows James’s plan to unfold—a scheme to steal four Arthur Dove paintings with a handful of hapless accomplices—what emerges is not a tale of precision but of slapstick ineptitude. The paintings don’t fit in the bags. A car gets stuck. Someone wears pantyhose on his head like a bad parody. At times the absurdity veers close to comedy, and Rob Mazurek’s restless jazz score underscores the chaos with sly energy, but the humor is always tinged with pity. When James tries to hoist a canvas into the rafters of a barn, stumbling and sweating as if wrestling with his own futility, the sequence stretches on deliberately, forcing us to sit with his incompetence. In another film this would be background business, the forgettable middle of a montage. In Kelly Reichardt’s hands, it becomes the essence of the story.

The brilliance of Josh O’Connor’s performance is how fully he embraces this contradiction. He plays James as a man whose every smile is a disguise, whose every boast is a lie half-believed. There is a twitchy charm to him at first—he tells his mother (Hope Davis) he needs money for an architectural project, assures his wife Terri (played with weary authenticity by Alana Haim) that work is coming soon—but behind the crooked grin sits a man terrified of becoming ordinary. O’Connor doesn’t make him monstrous. He makes him painfully, hilariously human. When he insists he is doing it all “for Terri and the boys,” you sense he believes it in that exact moment, even as he abandons those same boys at a bowling alley while he drives off to oversee his pathetic scheme. It is a performance built on micro-expressions, on the way his confidence collapses in silence, on the flicker of recognition that perhaps he was never the hero of his own story.

The supporting cast is quietly effective, though often sidelined by design. Alana Haim, so luminous in Licorice Pizza, is reduced here to fragments of exasperation, a woman too exhausted to fight but too perceptive not to see through her husband. Bill Camp, as James’s judge father, is formidable in just a few scenes, embodying the generational disappointment of a man who has long since stopped expecting anything but failure from his son. John Magaro and Gaby Hoffmann inject a sharp jolt of energy in the second half as old friends who expose James’s delusions with brutal clarity. The film’s quiet cruelty lies in how every character mirrors back to James what he refuses to see himself: that he is not an outlaw, not a rebel, not even particularly dangerous. He is just small.

The political backdrop of early 1970s America hums throughout the film like static. News reports about the Vietnam War play in kitchens, protestors march in the streets, and Richard Nixon’s paranoia seeps into the edges of suburban life. Kelly Reichardt never forces the allegory, but it’s impossible to miss. James, blundering through a plan he cannot control, convinced of his own cleverness while leaving wreckage in his wake, becomes a microcosm of a nation stumbling into catastrophe under the guise of authority. Like America itself, he puts on the mask of confidence but is revealed as brittle, reactive, and fundamentally lost.

Cinematographer Christopher Blauvelt, a longtime collaborator of Kelly Reichardt’s, frames this world with autumnal melancholy. The palette is all rust, mustard, and damp gray skies, as if the colors themselves are tired of pretending. Interiors feel suffocatingly dim, while exteriors capture the muted sprawl of small-town New England in a way that makes every road look like a dead end. The film could easily be mistaken for something pulled from the archives of 1970s New Hollywood, its unglamorous textures recalling John Huston’s Fat City or Sidney Lumet’s Dog Day Afternoon. Yet it is unmistakably Kelly Reichardt, her patience and eye for the mundane transforming even the act of hiding stolen art in a pigsty into a meditation on futility.

What lingers after The Mastermind is not the thrill of a robbery but the quiet devastation of watching a man unravel. One late scene finds James alone in a motel room, staring at news reports of his crime with something close to disbelief, as if he cannot quite connect the man on screen to the one sitting in the dark. In another, he mutters words to his reflection that the audience cannot hear. The content of the confession doesn’t matter. What matters is the rare flicker of honesty—perhaps the first time he has seen himself without a lie to lean on. Kelly Reichardt offers no redemption, no sudden burst of courage, no cathartic reckoning. Instead, she leaves us with the sense of a man drifting further from shore, and a country drifting with him.

For all its humor, The Mastermind is a profoundly sad film, one that treats failure not as spectacle but as a way of life. It may not satisfy those expecting the pulse of a traditional heist thriller, but in its slow accumulation of details—the way a child’s comment hangs in the air, the silence of a car ride with nothing left to say, the hollow bravado of a phone call—it becomes something richer. Kelly Reichardt has crafted a story about the aftermath rather than the act, about delusion rather than ambition, about how the mythology of American ingenuity can so easily collapse into farce. In doing so, she has also given Josh O’Connor one of the most quietly devastating roles of his career.

The irony of the title is the film’s enduring joke and its bitter truth. James Mooney is no mastermind. He is, at best, a man who confused impulse for vision, who mistook desperation for genius. And yet, in watching his inevitable downfall unfold, Kelly Reichardt captures something larger: the hollow space between who we think we are and who we truly become. That space, sad and absurd, is where The Mastermind lives—and it lingers long after the screen fades to black.

The mastermind

Directed by Kelly Reichardt

Written and Directed by Kelly Reichardt

Produced by Neil Kopp, Anish Savjani, Vincent Savino

Starring Josh O'Connor, Alana Haim, Hope Davis, John Magaro, Gaby Hoffmann, Bill Camp

Cinematography : Christopher Blauvelt

Edited by Kelly Reichardt

Music by Rob Mazurek

Production companies : Mubi, Filmscience

Distributed by Mubi (United States),

Release dates : May 23, 2025 (Cannes), October 17, 2025 (United States)

Running time : 110 minutes

Seen on September 7 2025 at the Deauville International Center

Mulder's Mark: