Movies - Stephen King and His Doubles: How Cinema Keeps Reinventing Him

By Mulder, 17 october 2025

There is a reason the name Stephen King sits like a quiet drumbeat under so much modern film and television: the work isn’t merely adaptable; it insists on it. Long before producers and streamers raced to option universes, Stephen King had already built one, brick by brick, in places with names that sounded like you might have passed them on a fogged-in New England road: Derry, Castle Rock, Jerusalem’s Lot. The biographical arc is familiar and still somehow startling—Stephen Edwin Stephen King, born in Portland, Maine, in 1947; the father who left; the long corridor of moves; the bookmobile driver who handed him William Golding’s Lord of the Flies and effectively lit the fuse; the mimeographed newspapers; the early magazine sales that paid a few bills and a lot of hope. But what matters for the screen is how early he began thinking in images—by his own account, “I loved the movies from the start”—and how that visual bias braided with a working reporter’s ear and a schoolteacher’s moral algebra. The result is prose that feels like camera setups: the establishing shot of a Maine town at dusk, the slow dolly toward a kitchen table where a glass of milk sweats on Formica, the hard cut to the thing in the drain. This is why his fiction keeps stepping off the page and into light.

The first wave of adaptations formed quickly after Carrie made the bookstores smell like something was burning. Brian De Palma’s 1976 film took Stephen King ’s tight, blood-humming debut and married it to split-screen bravura; it’s often remembered for the prom and the bucket, but the film’s endurance lives in how it understands the book’s two rails—adolescent cruelty and religious mania—as the same electricity. Four years later, Stanley Kubrick’s The Shining turned a haunted hotel into a geometry problem and, for better and for weirder, became both an aberration and a cornerstone in the Stephen King filmography. What gets lost in the familiar debate—book Jack vs. film Jack, alcoholism and redemption vs. maze logic and madness—is how Stephen King ’s “what-if” generator gave cinema an inexhaustible toy: lock a family in a hotel and see what the walls do. Even the disagreements between novelist and director underline a truth about Stephen King on screen: his premises are machines that will run under different drivers. When the compressor kicks on, Derry hums whether Rob Reiner is warming it for friendship and grief in Stand by Me or Frank Darabont is tuning it for institutional tenderness in The Shawshank Redemption and The Green Mile.

Across five decades, the data tell a story that matches the intuition. In a curated inventory of Stephen King’s screen work, there are 59 feature films and 40 television projects, giving us just shy of a hundred on-screen incarnations. The tempo is not uniform. The 1980s surge gave us 14 films, the 1990s added 13 more, and then—after an early-2000s dip—the 2010s returned with 13 films, a second wind some of us felt in the bones as It ballooned and burst across box offices. The small screen has its own rhythm: a modest start in the 1980s, a 1990s glut of miniseries, a contraction, and then the streaming era’s hunger for long-form world-building. Notably, the pipeline continues: 2025 alone stacks Oz Perkins’s The Monkey, Mike Flanagan’s The Life of Chuck, Francis Lawrence’s The Long Walk, and Edgar Wright’s new The Running Man; television pushes forward with It: Welcome to Derry and, in 2026, a fresh Carrie miniseries under Mike Flanagan. The pattern is clear: each generation of filmmakers tests its craft against Stephen King’s premises the way musicians work standards—same chart, new phrasing, different temperature.

If you look under the hood of the filmography, one detail stands out with the clarity of a headlight on snow: Stephen King travels to the screen not only as a novelist but as a master of the short form. Among the features, the split between novels and short fiction is almost even, with a slim lead for the novellas and stories. The television slate leans even harder on shorter works. This matters because it answers a tired complaint—that the “best” Stephen King movies only come from “non-horror” novellas like Rita Hayworth and Shawshank Redemption or The Body. The wider pile says otherwise. Short form is the torque that lets directors adapt theme without drowning in incident, the same way Stephen King ’s Different Seasons let him change musical keys without switching instruments. It’s not that novellas are magically “better”; it’s that a compact chassis invites cinematic invention. Rob Reiner’s two Stephen King classics, Frank Darabont’s two most beloved dramas, Zak Hilditch’s bruiser 1922—these aren’t escapes from Stephen King’s wheelhouse; they’re proof of it.

There’s also the matter of stewardship. Certain names recur often enough to feel like custodians. Frank Darabont gives us a triptych—The Shawshank Redemption, The Green Mile, and The Mist—that triangulates the Stephen King cosmos between hope, grace, and utter despair, the last of which yields one of the most divisive endings in mainstream horror. Mike Flanagan has quietly become the modern interpreter, reaching for emotional clarity without sanding off the weird: Gerald’s Game turned a “bottle” horror novel into a pressure cooker about marriage and memory; Doctor Sleep performed the impossible task of honouring Stephen King ’s novel while nodding at Stanley Kubrick’s film, braiding two discourses that had lived apart for decades. Mick Garris shepherded multiple miniseries, including the book-faithful The Shining and the apocalyptic sprawl of The Stand; his work underscores a counter-thesis to cinema’s hall-of-mirrors argument: sometimes the right place for a maximal Stephen King story is a long runway on television, not the two-hour squeeze of theatrical. Meanwhile, Andrés Muschietti showed that “big” horror can wear sentiment without apology in It and its sequel—childhood bonds as shield and wound; Rob Reiner proved that Stephen King’s tenderness can sit in the same chair as dread; George A. Romero reminded us that pulp and political funk belong in the stew; Lewis Teague found snap and velocity in Cujo and Cat’s Eye. Directors arrive, take what they need from Stephen King’s box of American anxieties—grief, addiction, small-town rot, the treacherous goodness of institutions—and leave a fingerprint.

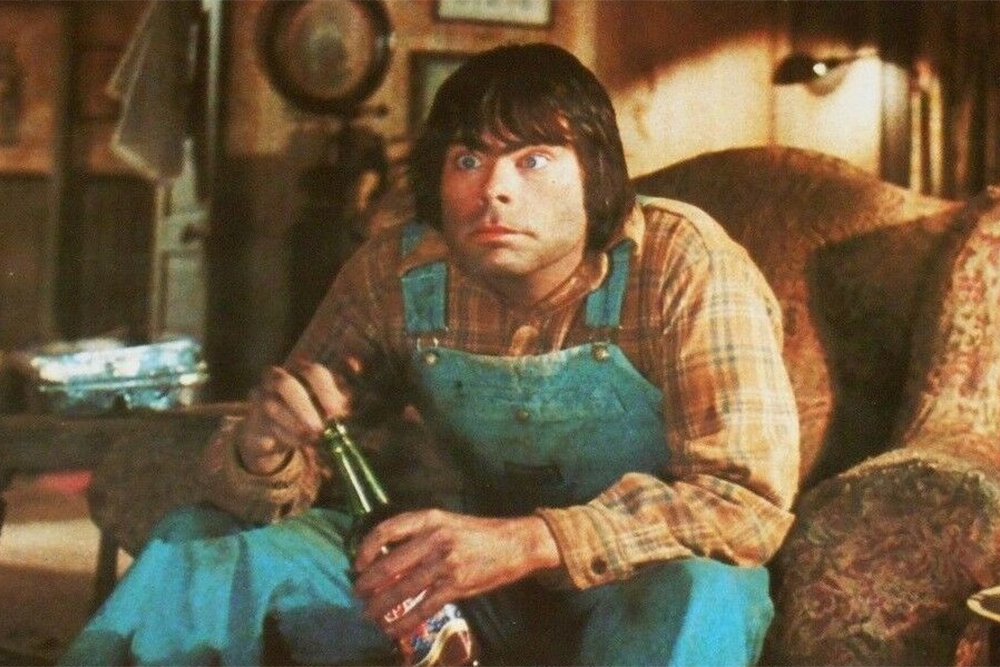

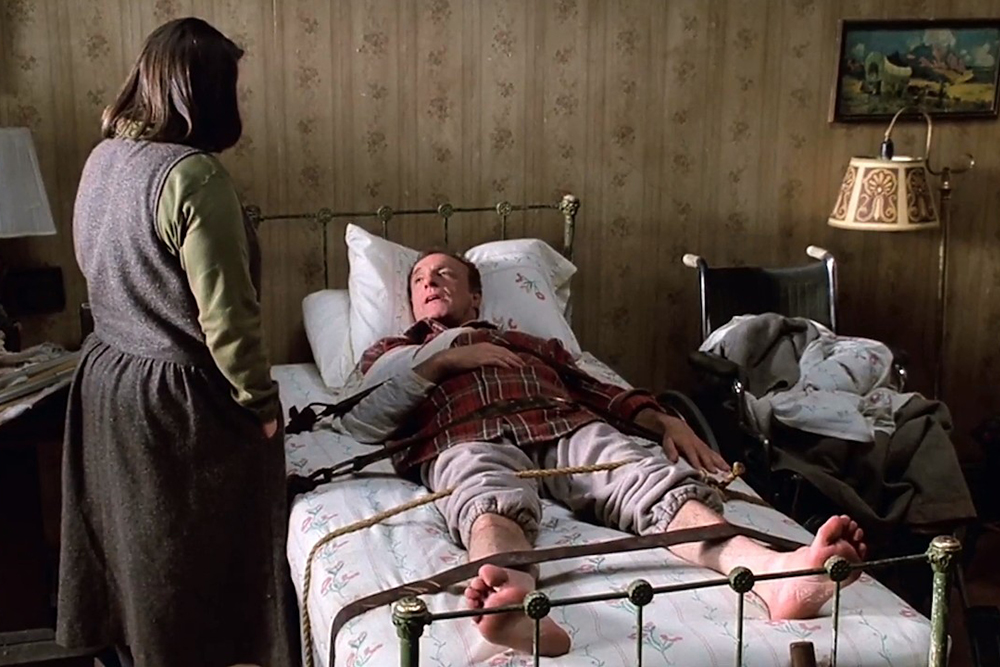

It helps to remember that Stephen King’s craft emerged alongside and was complicated by addiction, sobriety, and a near-fatal accident that could have ended everything. When Stephen King writes that he “barely remembers writing Cujo,” you feel a shiver moving through the filmography, not to malign the book or the taut 1983 film, but to notice how certain stories, once they reach the screen, seem to carry the residue of the grind that made them. The Tommyknockers wears its metaphor for addiction openly; Misery personifies captivity so nakedly that, decades later, you can still hear Kathy Bates say “I’m your number-one fan” and feel your ankles ache. The cinema gives these private wars a public echo. When Stephen King later writes On Writing, a book that’s half workshop and half moral inventory, it tangles backward with the movies—a reminder that the author behind the adaptations treats craft as a way of living: read a lot, write a lot, tell the truth about how people really behave when the extraordinary intrudes on the ordinary. Watch enough Stephen King films and you realize that this ethic—truth inside the lie—governs the good ones. The monsters are never just monsters; they are the algebra that reveals the sum in the people.

The geographic spell of Maine is another screen advantage disguised as a literary habit. Joyce Carol Oates noted how saturated Stephen King’s fiction is with that atmosphere—shorelines and mill towns, the muffled resentments in a diner at 2 p.m., the sanctimony in a church basement. On film, the place serves as a character without posing; you can smell the brackish water in Dolores Claiborne, feel the institutional damp in The Green Mile, and recognize the childhood summers in Stand by Me even if the coordinates are technically Oregon. The point isn’t cartographic accuracy; it’s emotional weather. When the movies drift elsewhere—The Running Man’s neon future, The Dark Tower’s desert myth—they still wear Stephen King’s small-town heartbeat like a metronome. That’s part of why even the oddballs are interesting: Stephen King ’s own Maximum Overdrive, messy and coked-through as he later admitted, is a roadside attraction because you’re watching the author try to shoot the way he sees. It doesn’t work by most measures; it still matters as a scrapbook page in the larger album.

If we pivot to adaptation mode and ask the industry’s practical question—what is easiest or “best” to adapt?—the Stephen King corpus gives a sly answer: respect the tone, and everything else is negotiable. The Shining’s book and film are famously unlike; both are canonical because both tell the truth of their respective makers. Doctor Sleep might be the most instructive case study because Mike Flanagan elected to harmonize Stephen King ’s novelistic resolution with Stanley Kubrick’s filmic architecture, staging a reconciliation between authorial intent and cinematic iconography. That effort—earnest, haunted, slightly miraculous—resembles the broader Stephen King screen tradition, where departures coexist with fidelities. Frank Darabont’s choice to invert the ending of The Mist is not a betrayal of Stephen King’s optimism so much as a dare: what happens if the fog doesn’t lift? These variations work because they keep faith with Stephen King’s central gambit: the extraordinary intrudes; the measure of us is what we do next.

There’s also the pipeline from page to French-language readers and back out into international adaptation culture, a loop that matters more than people think. The French publication history shows Albin Michel acting as a long-term engine for Stephen King’s presence, with the first French Stephen King book hitting shelves in 1976 and the stream continuing into the present. This sustained translation ecology does more than supply bookstores; it seeds film culture with a shared text. It’s part of why references land and why rooms of French critics debate It with the same fluency as Shawshank or Misery; the books have been living in the language the whole time. Add to this the way French titles sometimes sharpen or tilt the angle of approach—Shining, l’enfant lumière—and you can see how each market refines the legend as it goes. That thickness of availability—novels, short stories, digital editions—helps explain why new adaptations keep coming: the readership replenishes the viewership.

Anecdotes—small, human, grounding—tend to travel with Stephen King and stick to the movies. The image of Tabitha Stephen King pulling the first pages of Carrie out of the trash is more than cute origin myth; it tells you that Stephen King, for all his facility, works under the pressure of doubt like everyone else, and that his career is in part a marital collaboration—something he nodded to when he called Lisey’s Story his favourite and described marriage as its own secret world. The story of Stephen King being hit by a van in 1999, nearly losing his leg, and then crawling back to the desk to finish On Writing reframes the quiet urge that animates the best screen versions: survival and meaning after impact. There’s the practical gag of Rob Reiner naming his company Castle Rock—proof that a fictional geography could become an industry address. There’s Roger Ebert softening to Stephen King’s literary reputation after reading On Writing, a cultural détente that put a generation of film-school snobbery on notice. There’s Peter Straub recalling how only Neil Gaiman could truly tell which sentences in The Talisman belonged to whom. These anecdotes aren’t trivia; they form a secret commentary track under the movies: collaboration, endurance, and a relentless insistence on story over posture.

The politics and public witness are part of the screen story too, not because they change how a camera frames Derry’s storm drains, but because they clarify the ethical source of the fiction. Stephen King has rarely hidden his views—on wealth and taxation, on guns, on publishing consolidation, on elections. Agree or disagree, you can feel in the narratives a throughline: power unaccountable is the real monster. The bully in Carrie, the warden in Shawshank, the company men in The Mist, the condescension of “respectable” townsfolks in It—all of them wear the mask of the ordinary, and all of them reveal a structural rot. Screen adaptations that land tend to keep this in focus. Even when the bogeyman is supernatural, the town did a lot of the work for him.

One of the most useful ways to read the filmography is to treat it as a long classroom exercise in Stephen King’s own craft advice. He starts with situation—what if a writer is trapped with his fan, what if a time portal opens behind a diner, what if a grieving man finds a burial ground that returns what it takes—and then he lets the characters show him who they are. On screen, this translates into a priority list. The adaptations that breathe don’t just reproduce plot; they stage a pressure chamber and trust the cast. Kathy Bates and James Caan are a locked duet in Misery; Tim Robbins and Morgan Freeman conduct patience in Shawshank; Sissy Spacek and Piper Laurie turn a kitchen into a battlefield in Carrie; Bill Skarsgård articulates appetite in It without ever letting the digital seams do all the work. The lesson is steady: the monsters are metaphors, but they only sing when the actors play the humans like they might break.

Because the corpus is so large, it can be tempting to sort it into winners and misfires and leave it at that. But there is a subtler pleasure in tracing how themes mutate across mediums. Addiction is bright and loud in The Shining, barbed and funny in Doctor Sleep, threadbare and sad in The Dark Half, literal and cosmic in Revival. Grief is private in Pet Sematary, communal in It, procedural in The Green Mile. Childhood, Stephen King’s most durable obsession, is a golden hour that the camera loves—Stand by Me and It ride this anachronistic light—and the best adaptations carry Stephen King’s conviction that kids form militias against the world, binding themselves for the long haul with oath and myth. When those bonds are broken, the horror lands with a thud you can feel under your ribs. That’s not an accident. Stephen King starts as a realist who believes in ghosts. The screen works when it believes this too.

The pipeline ahead looks almost greedy, but it’s really just logical exhaustion: with so much catalogue—novels, novellas, short stories, pseudonymous thrillers—there will always be another angle. Seeing Francis Lawrence tackle The Long Walk in 2025 makes a kind of sense; he knows how to direct bodies under rules. Edgar Wright circling The Running Man feels like an argument with media spectacles as fresh as tomorrow’s algorithm. Oz Perkins tends the funhouse where dread is a flavour, which bodes well for The Monkey. And Mike Flanagan seems less like a single adapter and more like an ongoing conversation partner; the slated Carrie miniseries hints that some stories are rituals the culture is not done performing. The streamers’ appetite for series—It: Welcome to Derry being the most obvious—might read as IP mining to the cynical. But it also reads as penance for decades when the two-hour frame pinched the breath out of longer Stephen King structures. The hope is not for slavish fidelity but for the right scale: some fears need more room to echo.

Numbers don’t explain art, but they can sharpen the outline. In the film slate, novels and short fiction partage the stage; on television, shorter works dominate, with five projects built from original Stephen King teleplays. Directors with the most entries—Frank Darabont, Mike Flanagan, Mick Garris—are also the ones most aligned with Stephen King’s ethic: empathy first, then horror. The adaptation curve peaks in the 1980s and 1990s, dips, then climbs again in the 2010s and beyond, matching both technological waves and audience cycles of appetite for fear. The French publishing trail, driven chiefly by Albin Michel, underscores an international readership that keeps renewing the warrant for new films. And the anomaly in any database—say, a line where 1922 the title seems to become 1922 the year—doubles as a metaphor for Stephen King on screen: the text keeps sliding into image until the image insists on being its own year.

In the end, the reason Stephen King persists in adaptation is neither mystical nor purely commercial. It’s practical: he tells the truth inside the lie with a clarity that cameras can use. He gives filmmakers situations that crack people open. He supplies a vernacular America—a factory town, a quiet kitchen, a school hallway—that can hold the weight of the uncanny without collapsing. He does all of this while admitting, on the page and in interviews, that stories are found things, dug up like fossils, sometimes small as shells, sometimes tyrannosauric. Cinema, for all its budgets and armies, is a tool for excavation. When it meets a Stephen King story, it has a good chance of pulling the bones out intact.

Maybe that’s the final anecdote worth keeping close. Stephen King once said that if you want to be a writer you have to read a lot and write a lot. Film is its own way of reading the culture out loud, and the Stephen King adaptations—good, bad, uneven, unexpectedly tender—function as collective annotations. They show what happens when the extraordinary knocks on the door and the ordinary, with all its flaws and loves, decides whether to answer. That’s why a boy can walk along train tracks in Stand by Me and why a killer clown can whisper in a storm drain in It and why both images feel like they belong on the same reel. The country changes; the face paint flakes; the hotel carpets get replaced; the prison walls turn the colour of a new decade’s hope. What doesn’t change is the thing Stephen King has been doing from the beginning: pointing to the place where the known world ends and asStephen King, with terrible kindness, if we want to look.

Stephen King Movie Adaptations – Filmography::

1976 - Carrie (directed by Brian De Palma)

1980 - The Shining (directed by Stanley Kubrick)

1982 - Creepshow (directed by George A. Romero)

1983 - Cujo (directed by Lewis Teague)

1983 - The Dead Zone (directed by David Cronenberg)

1983 - Christine (directed by John Carpenter)

1984 - Children of the Corn (directed by Fritz Kiersch)

1984 - Firestarter (directed by Mark L. Lester)

1985 - Cat's Eye (directed by Lewis Teague)

1985 - Silver Bullet (directed by Daniel Attias)

1986 - Maximum Overdrive (directed by Stephen King )

1986 - Stand by Me (directed by Rob Reiner)

1987 - Creepshow 2 (directed by Michael Gornick)

1987 - The Running Man (directed by Paul Michael Glaser)

1989 - Pet Sematary (directed by Mary Lambert)

1990 - Tales from the Darkside: The Movie (directed by John Harrison)

1990 - Graveyard Shift (directed by Ralph S. Singleton)

1990 - Misery (directed by Rob Reiner)

1992 - Sleepwalkers (directed by Mick Garris)

1993 - The Dark Half (directed by George A. Romero)

1993 - Needful Things (directed by Fraser Clarke Heston)

1994 - The Shawshank Redemption (directed by Frank Darabont)

1995 - The Mangler (directed by Tobe Hooper)

1995 - Dolores Claiborne (directed by Taylor Hackford)

1996 - Thinner (directed by Tom Holland)

1997 - The Night Flier (directed by Mark Pavia)

1998 - Apt Pupil (directed by Bryan Singer)

1999 - The Green Mile (directed by Frank Darabont)

2001 - Hearts in Atlantis (directed by Scott Hicks)

2003 - Dreamcatcher (directed by Lawrence Kasdan)

2004 - Secret Window (directed by David Koepp)

2004 - Riding the bullet (directed by Mick Garris)

2007 - 1408 (directed by Mikael Håfström)

2007 - The Mist (directed by Frank Darabont)

2009 - Dolan's Cadillac (directed by Jeff Beesley)

2009 - Everything's Eventual (directed by J. P. Scott)

2012 - Willa (directed by Christopher Birk)

2013 - Carrie (directed by Kimberly Peirce)

2014 - A Good Marriage (directed by Peter Askin)

2014 - Mercy (directed by Peter Cornwell)

2016 - Cell (directed by Tod Williams)

2017 - The Dark Tower (directed by Nikolaj Arcel)

2017 - It (directed by Andrés Muschietti)

2017 - Gerald's Game (directed by Mike Flanagan)

1922 - 1922 (directed by Zak Hilditch)

2018 - The Doctor's Case (directed by James Douglas et Leonard Pearl)

2019 - Pet Semetary (directed by Kevin Kölsch et Dennis Widmyer)

2019 - It: Chapter Two (directed by Andrés Muschietti)

2019 - In the Tall Grass (directed by Vincenzo Natali)

2019 - Doctor Sleep (directed by Mike Flanagan)

2022 - Firestarter (directed by Keith Thomas)

2022 - Mr. Harrigan's Phone (directed by John Lee Hancock)

2023 - The Boogeyman (directed by Rob Savage)

2023 - Pet Sematary: Bloodlines (directed by Lindsey Beer)

2024 - Salem's Lot (directed by Gary Dauberman)

2025 - The Monkey (directed by Oz Perkins)

2025 - The Life of Chuck (directed by Mike Flanagan)

2025 - The Long Walk (directed by Francis Lawrence)

2025 - The Running Man (directed by Edgar Wright)