Prime-Video - 7500, discover a great new thriller

By Mulder, 26 may 2020

A heart-pounding and thought-provoking thriller from Oscar-nominated director Patrick Vollrath (Everything Will Be Okay), 7500 stars Joseph Gordon-Levitt (Inception, 50/50, Batman The Dark Knight Rises), Omid Memar (A City Hunts a Murderer, Blutige Anfänger), Aylin Tezel (“Tatort,” “X Company”), Carlo Kitzlinger (Berlin, I Love You, Devil’s Daughter), Murathan Muslu (“CopStories,” “Skylines”) and Paul Wollin (“Dogs of Berlin,” Toro). The film is written by Vollrath and Senad Halilbasic (Of Sound Mind, Hypotopia). Award-winning producers are Jonas Katzenstein (Ana, Mon Amour; Hunting Season) and Maximilian Leo (Ana, Mon Amour; Hunting Season). Executive producers are Ellen Goldsmith-Vein (The Maze Runner, Abduction) and Lindsay Williams (The Maze Runner, Camp X-Ray). Co-producers are Alexander Glehr and Franz Nowotny. The director of photography is Sebastian Thaler (Falling, Ugly). Casting is by Anja Dihrberg (The Captain, 3 Days in Quiberon). Production designer is Thorsten Sabel (It’s Your Turn, Honey!; Marry Me). Costume designer is Christine Zahn (Right Here Right Now, Boy 7). Key makeup is by Samira Ghassabeh (Bonnie & Bonnie, “Tatort”). The film is edited by Hansjörg Weissbrich (Colonia, What to Do in Case of Fire). Supervising sound editor is Daniel Iribarren (“Unorthodox,” A Fantastic Woman).

After the overwhelmingly positive response to the Cannes premiere of his 2015 short film Everything Will Be Okay, German-born writer-director Patrick Vollrath found himself fielding the same question from industry honchos on both sides of the Atlantic: What are you going to do next?

Vollrath had a number of ideas for his first feature film, but one in particular — a hijacking thriller set almost entirely in a commercial airliner cockpit — sparked the interest of award-winning producing duo Jonas Katzenstein and Maximilian Leo. After reading the director’s two-page outline, the pair thought it was a perfect fit for their Cologne-based production company, augenschein Filmproduktion, which focuses on films with both cultural and commercial value.

Before any papers were signed, however, Vollrath fleshed out the story, which culminates in the forging of an unexpected bond between one of the pilots and a teenage hijacker, in a 30-page treatment he wrote on spec. “I wanted to make sure we were all on the same page about the film I wanted to make,” he explains. “When they read it Jonas and Max said, yeah, that’s something we’re really interested in and we want to give you a contract to write the screenplay. They were very supportive and gave me complete creative freedom, which was the most important thing to me.” More doors opened for Vollrath in early 2016, after Everything Will Be Okay was nominated for an Academy Award® for best live-action short. During his trip to Los Angeles to attend the Oscar ceremony he met with A-list American actors for the lead role of the mild-mannered pilot who finds himself in a terrifying situation.

Returning to his home in Vienna, Vollrath completed the script and the search for financing began in earnest. Initial funds came from the German and Austrian governments. “It was state funding so there were no creative strings attached,” says the director. “That was a very good starting point to make a film that is so director driven.” In May 2019 Amazon Studios acquired global distribution rights to the completed film.

The Anti-Bruce

In casting the central role of Tobias, Vollrath says he was looking for a talented actor in his 30s, who was likeable and convincing as an up-and-coming airline pilot. What he didn’t want was a typical action hero. “I was very much looking for not a-Bruce Willis-kind of guy,” he says. “Not a Special Forces-trained guy who can use all his abilities to solve the situation. Tobias is an everyman who never expects to be in a situation like this and hopes he never will be — and then it happens. So he’s as overwhelmed as you or I would be.” Vollrath also wanted an actor with whom viewers could easily empathize. “He had to be someone the audience likes from the moment he enters the cockpit,” he explains. “So we’re on his side even when he has to make some incredibly difficult decisions.” Joseph Gordon-Levitt checked all the boxes for Vollrath, who reached out to the two-time Golden Globe nominee through his reps. Although Gordon-Levitt says he loved the script, it was watching Everything Will Be Okay that convinced him to meet with Vollrath about the part. “It’s a really brilliant short film,” says Gordon-Levitt, whose starring roles have included 500 Days of Summer, 50/50 and Inception. “All of the performances felt so natural. I found watching it to be incredibly emotional, and it really drew me in because it felt like I was watching something real — except it looked like a beautiful movie, not a documentary.” During their meeting, Vollrath described the unconventional process he had used to film Everything Will Be Okay. “He explained how it involved a lot of improvisation on the part of the actors as well as on the part of the camera,” recalls Gordon-Levitt. “And letting the camera roll for 20, 30 or even 40 minutes at a time and just letting the actors become the characters and live the situation.” Vollrath said he planned to shoot 7500 (the title refers to the air traffic control code for a hijacking) using the same improvisational style. “For me, it’s not really important exactly what you say or even what you do, it’s more about the emotion underneath it,” says the director. “Just go with your emotion, go with the character, what you think he would do, what you feel in the moment. Then we look at it and I either say, I think that’s too much, or that’s a direction I really love, can you explore that a little bit more in the next take? And then we do it again for 30 minutes. We do it four, maybe five times, and then the shooting day is pretty much over.” Gordon-Levitt says it was an approach unlike anything he had ever experienced and he was immediately intrigued by the challenge. “That was a big part of why I wanted to do the movie,” he says. “I love trying something I haven’t done before. But it turned out to be more than just a fascinating creative process to participate in. You can see when you watch the movie that there’s a realism and an intensity that’s quite unique. It doesn’t feel like any other movie.”

This Is Your Captain Speaking

For the role of Michael, the ill-fated flight’s pilot, Vollrath cast German actor Carlo Kitzlinger. Although he had few screen credits to his name, Kitzlinger’s resume included experience the director considered even more valuable for the role: two-plus decades piloting planes for Lufthansa. The verisimilitude and confidence Kitzlinger brought to the role would be difficult for an actor to replicate, says Vollrath. “There’s a lot of routine that comes with being an airline pilot. We looked for actors who we could coach so they could really embrace that and learn it. But at the same time, I told the casting director to look for someone who was actually a pilot. And that happily came together.” In addition to playing the role of Michael, Kitzlinger was recruited to help teach Gordon-Levitt some of the technical aspects of flying a commercial passenger jet. The pair spent two weeks in flight simulators in Germany, including time in the one Lufthansa pilots are required to train on regularly. “Normally, if you’re playing a pilot in a movie you only have to do little bits of it at a time, and then they edit it together and make it seem real,” observes Gordon-Levitt. “But Patrick wanted to do an entire takeoff sequence and just leave the camera rolling the whole time. So I had to learn all of the things a pilot does before and during takeoff.” Beyond schooling him in the technical minutiae, Gordon-Levitt says having a veteran pilot seated next to him during production was invaluable when it came to understanding a pilot’s behavior in the cockpit. “I had a million questions about cultural things. Like, do you ever use these little footrests? Would you ever take out your phone and send a text message at this point in the sequence? Are pilots pretty relaxed at this point or are they more at attention? It was incredibly helpful to be able to just turn to the guy on my left and ask him things like that.”

The Search for Vedat

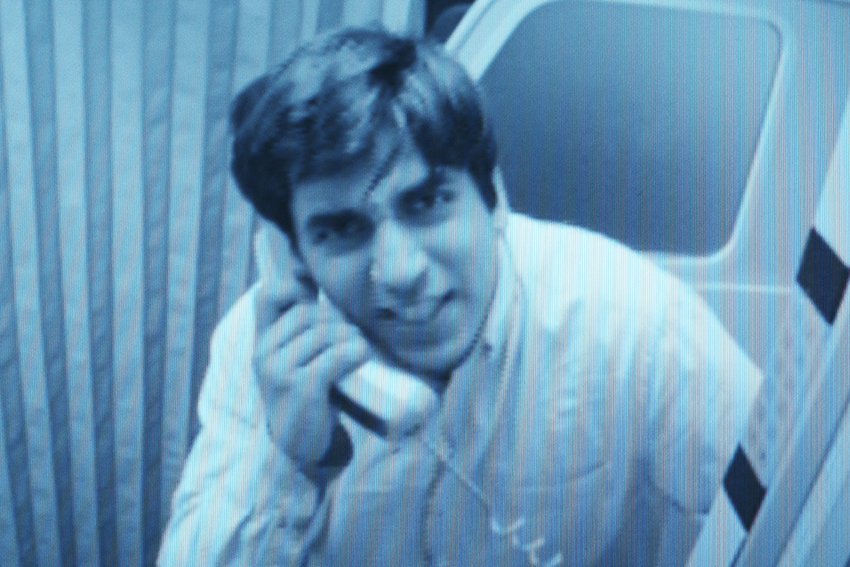

The film’s third main character is Vedat, the youngest of the terrorists. Vollrath says the idea for the character came to him after seeing news coverage of people ISIS had recruited from their safe lives in Europe to go fight in Syria. “I saw a report about a young boy, not older than 18, born and raised in Germany, who had joined the Islamic State in Syria. But when he came back home he realized how wrong he was. The look in the young boy’s disillusioned face moved me and inspired me to create the character of Vedat.” Finding a young actor to play the nuanced role of a terrified teenager who is in over his head turned out to be a tall order. “I wanted someone young, on the verge of becoming an adult but still kind of a child,” says the director. “It didn’t have to be someone Middle Eastern or Arab, but because it’s a part of the story, I wanted someone who grew up in Germany but was not originally from there — or whose parents were not originally from there. Someone who has integrated into society but doesn’t feel integrated because the society doesn’t really accept him as German.” The filmmakers put the word out to casting agencies in multiple countries and even conducted street casting to find someone who could project the right combination of fanaticism and naiveté, while portraying the intense emotions the character experiences as he grasps the full weight of his situation. “We asked each of the actors to audition the hardest scene — where they have to cry on one side and be aggressive on the other side,” says Vollrath. The production received more than 200 videos from hopeful actors, but one, from a then-18-year-old Austrian named Omid Memar, stood out to Vollrath. “I was traveling in Hong Kong and our casting director sent me a link to his audition tape. I was on the street and sat down on a bench and watched it. Omid nailed the scene and even though I was in this very crowded place, I was really moved.” Once the actor was cast, Memar and Vollrath began a series of long conversations about Vedat. “I tried to be open and hand over the character to him and hoped that between who he is and his acting, something unique or something personal would come to life, and it did.” Gordon-Levitt is effusive in his praise for Memar’s work in the film. “It’s exciting to see a talented new young actor give such a powerful and honest performance,” he says. “He’s just fantastic. For anyone who appreciates good acting, I’d recommend watching this film just to see him.”

Opening the Door

With the exception of the opening sequence, a series of shots from the perspective of airport terminal surveillance cameras, 7500 takes place entirely in the cockpit of an Airbus A320 airliner. “It’s fascinating to see how you can tell a whole story without moving from a confined space,” observes Gordon-Levitt. “In more conventional moviemaking a lot of the storytelling comes from the different locations you shoot in. And so to take away that variable was another really interesting creative challenge I hadn’t been a part of before. But it’s also a powerful metaphor.” To Gordon-Levitt, the locked door that separates the hijackers from the pilots can be seen as a symbol for the way a subset of Western society, including immigrants, are kept out of the driver’s seat — and the way frustration about that can sometimes erupt in violence. “They’re not in control of their own lives or where they’re going and they’re trying to fight for that control.” Vollrath also notes that for most of the film, Tobias can only see the hijackers as blurry figures on a grainy black-and-white camera monitor. “It’s similar to the images we all know from the media when it comes to terrorism — videos from surveillance cameras or poor-quality propaganda recordings that don’t reveal the bigger picture.” Once the physical door dividing them is opened, however, and Tobias and Vedat come face to face, they form an unexpected bond. “That’s really the crux of the movie to me,” says Gordon-Levitt. “That once you put two human beings in a room together, and they are no longer relating to each other as labels, as stereotypes, they have to relate to each other just as people and find what they have in common.” There’s Nothing Like the Real Thing Vollrath’s commitment to authenticity led to the production purchasing an actual airliner to film in. “We had to buy a real airplane because none of Europe’s mock-up planes could convince Patrick,” says producer Leo. “Not one of them looked exactly like a real A320 or a Boeing. Instead they all looked like combinations of the two. So, we bought a real one, cut it and used the front third of the plane. In the end, it was worth it because it feels more realistic than anything I have ever seen on screen.” Of the two major aircraft makers, Vollrath wanted an Airbus because the way the flight controls are configured matched certain key elements of his screenplay. Finding one for sale turned out to be a challenge, however. “Through a connection here and a connection there we found a company that buys and rebuilds airplanes for training flight attendants and airport security,” he says. “There we found a decommissioned Airbus A320 which was exactly what I wanted.” The segment of the aircraft used for filming included the front galley (food-prep area) and the first eight rows of seats, but it had no flight instruments, so the art department had to buy or rebuild those. “It turns out there is this huge community of geeks who are into flight simulators and build airplane instrument panels in their basements,” says the director. “So it was a matter of getting in touch with people who referred us to other people who could sell us what we needed.” After that, the task of making the intricate controls look accurate fell to production designer Thorsten Sabel and his team. “Some things, like the door-lock button, which is really hard to get, they had to build from scratch,” says Vollrath. “There’s a good page on the Airbus website where you have a 360-degree view inside a cockpit and you can zoom in. I always had that on my phone and I’d be like, ‘It has to look like this.’” The airplane segment was moved to a studio in Cologne where it was positioned about 12 feet above the ground on a pneumatic rig that allowed it to be shaken by hand to simulate the plane’s vibrations as it encounters turbulence or makes steep ascents or descents. “Someone was literally standing next to it and shaking it,” says Vollrath. “We weren’t depending on anything electrical.” Almost the entire film was shot in the studio, using front projection and blue screen for whatever takes place outside the plane’s windshield. The only exception was the film’s final scenes, for which the cockpit was moved to an actual airfield and the outside action was filmed live.

Camera Dance

As part of his extensive research prior to the shoot, cinematographer Sebastian Thaler spent time filming in the cockpit of an actual commercial airline flight, capturing footage that would serve as a visualreference for all of the departments on set. “We took a small camera with us and documented all the work in progress by the pilots as well as the lighting conditions,” he recounts. “That became sort of a mood board for everybody — for the art department, for us, for the lighting folks. And we tried to reproduce this documentary feeling we had in the real flight cockpit with our studio cockpit.” The confined set, along with the improvisational nature of the acting, posed numerous challenges for Thaler. “There was no real written dialogue, except for the technical stuff,” he says. “Everything else was improvised by the actors with Patrick’s guidance. And the movement was also free, so I didn’t know if or when they were going to stand up or sit down or what they were going to do. So that was all happening live in front of me without any rehearsal.” In order to respond instantaneously to the improvised action, all of the camerawork was handheld. And because of the limited space, Thaler was the only crew member positioned inside the cockpit. Lights were placed throughout the cockpit and turned on and off by a lighting operator on the fly to avoid the cameraman casting any unwanted shadows. Focus pulling was also handled remotely via a video monitor. The sound team strategically positioned mics so they could capture the dialogue wherever the actors moved. The film was shot digitally to allow the extended takes to play out without the need to stop and change film canisters. Thaler chose the ultralight Alexa Mini to give him maximum maneuverability. “There was only one spot in the back of the cockpit where I could stand so I had to have the camera in front of me the whole time rather than on my shoulder,” he explains. “I needed the smallest possible camera.” The filmmakers initially considered shooting in a 1.85:1 aspect ratio but eventually decided on 2.35:1. “We talked about using the more vertical frame to convey the claustrophobia of the setting, but after some test shooting we found there was too much information at the top and bottom of the image,” says Thaler. “You saw too much of the cockpit, which was distracting from the actors.” Lenses typically ranged from 18mm to 35mm focal lengths, with occasional wider-angle shots. During filming, Vollrath provided direction to his cinematographer through an earpiece. “I was choosing what was important to show the audience at each moment,” says Thaler. “Sometimes Patrick would tell me what he wanted to see or something he wanted to try out. But sometimes I ignored him. We’ve known each other so long that I know he trusts me and I trust him.” After each take, director and cinematographer would huddle in the video village to analyze the footage and discuss any changes for the next take, says Thaler. “Maybe we wanted to use a closer lens to have more possibilities for editing. Or maybe we would decide to concentrate more on this part or more on that part of the scene.”

Making the Cut

Veteran editor Hansjörg Weißbrich was on set during the entire shoot in the Cologne studio and met with the director each evening to discuss what had been filmed that day. A major challenge for editor and director was determining which moments out of each of the sometimes hour-long takes were the most compelling. “It was almost like a documentary, where we had to winnow down the footage,” says Weißbrich. “Eventually we decided Patrick would make a preselection of the parts he liked and then we’d cut it down to those basic moments. At that point it was basically about focusing and tightening. The story is very intense, and the acting was very intense — Joseph did a fantastic job — so we just picked the most intense moments and combined them in a way that the suspense is highest.” The vast amount of footage also allowed Weißbrich to let some scenes play out for long periods uncut, with a single camera angle; others use jump cuts or reverse points of view. “It’s about the overall rhythm, you have to alternate to keep up the emotion level,” he notes. “For example, the opening scenes with Tobias and Michael are cut back and forth. And the door to the cockpit is open, so you have the action in the cabin seen from the cockpit. But then the takeoff process is very much one take. It’s also a shot where the whole background outside has been created digitally.” Because the actors were constantly improvising, Weißbrich often had to figure out how to deal with continuity issues between different takes. “Things like headphones on, headphones off; left hand, right hand; shirt sleeves rolled up or rolled down,” he explains. “But because we used a jump-cut, almost documentary style of editing where we establish small jumps in time rather than creating a classical continuity of action, those issues don’t really matter the way they would with a more traditional editing style.”

Sound and Fury

Vollrath studied filmmaking with acclaimed Austrian director Michael Haneke, whose naturalistic films typically eschew musical scores. In 7500 , Vollrath chose to go a similar route, using only noises generated by the aircraft and its inhabitants to create the film’s evocative soundscape. “Music manipulates you and tells you what to feel,” says the director. “In some movies, it’s great, because it gives you a very strong emotion you wouldn’t have without the music. But for this film, I wanted there to be a very close relationship between the actors and the audience without any underlying music. At the same time, I had the idea we could create a lot of suspense from the sound design, so we built some kind of musical elements from that.” For supervising sound editor Daniel Iribarren, that presented the challenge of creating a dynamic soundtrack with a limited sound palette set against the airplane’s almost constant ambient noise — while still ensuring the dialogue was clearly understandable. Just accurately emulating the background noise inside an Airbus cockpit was no easy feat. Although he was unable to embed himself in a cockpit because of security regulations, Iribarren managed, through personal connections, to give small digital recorders to pilots who agreed to capture the in-flight sounds. Those recordings were combined with sounds created digitally using BOOM Library’s Turbine plug-in software to create the roar of the jet engines. Those are then varied in pitch and volume depending on the speed and trajectory of the plane at various points in the film. Kitzlinger, the pilot turned actor and technical adviser, helped Iribarren ensure the interior sounds generated by the flight system — many of which were recorded by the foley team on set — were true to the specific Airbus model. “All the clicky, non-digital sounds from the instrumental panel had to be very precise,” says Iribarren. Beyond the meticulous work of simulating the airplane noises, Iribarren collaborated with Vollrath to underscore the emotional impact of certain scenes through sound design and mixing. For instance, after the

murder of Tobias’ girlfriend, Gökce, the sounds of the plane fade away as the pilot tries to steady himself and contemplate his next move. A little later in the film, the attackers’ rhythmic, near-constant pounding on the cockpit door builds the tension to a fever pitch. “That was a painstakingly long process of finding rhythms and sounds that worked dramatically,” says Iribarren. “I layered sounds and then I’d have Patrick listen to them. Sometimes he’d ask me to speed it up a little bit or slow it down or add some pauses. So that’s an example of the musicality of the sound design. But at the same time it’s true to what’s happening dramatically — where the terrorists were positioned, their sense of panic at that time, etc.”

Breaking the Cycle

Although Vollrath has created a visceral, edge-of-your-seat thriller, he hopes once viewers’ heart-rates subside they will ponder the bigger questions the film poses. “Revenge is often the first urge when an unprovoked act of violence costs innocent lives,” he says. “To counter violence with violence is a very human reaction that cannot only be felt by individuals but by society as a whole. 7500 explores the dynamics of this vicious cycle and asks one of the toughest questions today: How can we break the circle of violence?” Vollrath says part of the movie’s aim is to show that there are human faces behind the masks of the terrorists, faces that are as misguided and despairing as they are brutal and dangerous. “Very often it is the feeling of being ignored or neglected that makes people cross this point of no return and commit terrible deeds — deeds that destroy any sympathy people could have had for them.” But, he says, as strong as the impulse for vengeance is, and as difficult as it is for victims and loved ones to turn the other cheek, in the end revenge doesn’t fix anything. “As Gandhi is quoted as saying, ‘An eye for an eye leaves the whole world blind.’”

Synopsis :

It looks like a routine day at work for Tobias, a soft-spoken young American co-pilot on a flight from Berlin to Paris as he runs through the preflight checklist with Michael, the pilot, and chats with Gökce, his flight-attendant girlfriend. But shortly after takeoff, terrorists armed with makeshift knives suddenly storm the cockpit, seriously wounding Michael and slashing Tobias’ arm. Temporarily managing to fend off the attackers, a terrified Tobias contacts ground control to plan an emergency landing. But when the hijackers kill a passenger and threaten to murder more innocent people if he doesn’t let them back into the cockpit, this ordinary man faces an excruciating test.

7500

Directed by Patrick Vollrath

Produced by Maximilian Leo, Jonas Katzenstein

Screenplay by Patrick Vollrath

Based on Patrick Vollrath, Senad Halilbasic

Starring Joseph Gordon-Levitt, Aylin Tezel, Aurélie Thépaut, Carlo Kitzlinger, Paul Wollin

Cinematography : Sebastian Thaler

Edited by Hansjörg Weißbrich

Production companies : MMC Studios, Augenschein Filmproduktion, FilmNation Entertainment, Endeavor Content

Distributed by Amazon Studios (United States), Universum Film AG (Germany/Austria)

Release date : August 9, 2019 (Locarno), June 19, 2020 (United States)

Running time : 92 minutes

Countries : Germany, Austria, United States

(Source : press release)