Interview - Dooba Dooba : When Fear Becomes a Ritual — A Conversation with Ehrland Hollingsworth

By Mulder, Los Angeles, 18 october 2025

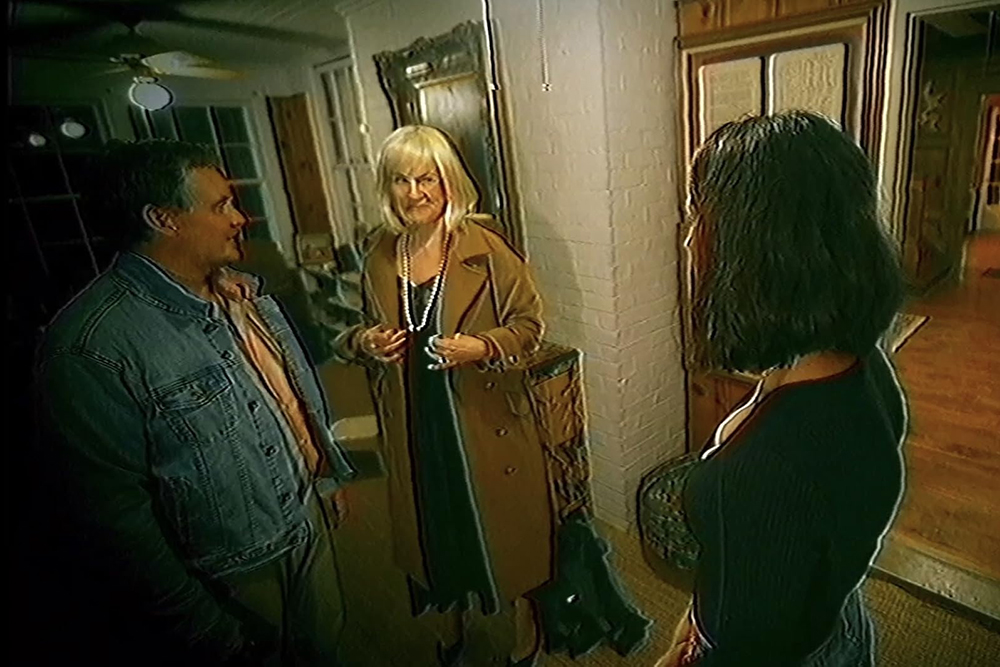

Premiering at the 2025 edition of Screamfest, Dooba Dooba instantly stood out as one of the festival’s most provocative and unsettling entries. Shot entirely through home-security cameras and low-resolution footage, the film blurs the line between surveillance and storytelling, exploring the dark spaces between control, fear, and human fragility. Following its Los Angeles premiere, we had the chance to sit down with writer and director Ehrland Hollingsworth to discuss the creative process behind this hypnotic descent into domestic paranoia.

Q: Dooba Dooba feels both absurd and hypnotic from the very first frame. What was the original spark — an image, a phrase, or a feeling — that led you to make this film ?

Ehrland Hollingsworth: The original sort of spark… well, I wanted to do something from security cameras, and security cameras have this very eerie angle, and I think the feeling just sort of, like, right off the bat, this kind of, like, high-angle stuff. And that was sort of like, can you translate that feeling into a feature film and then sort of overlay on top of that the aesthetics of YouTube analog horror, which I think is very effective at this particular sense of dread? And so those were kind of the two things as far as the tone I was trying to achieve.

Q: The title phrase becomes almost a ritual chant throughout the film. Where did it come from, and what does it represent to you as the story unravels ?

Ehrland Hollingsworth: Well, Dooba Dooba is kind of this very innocent word, and it’s sort of like baby babble. Initially, to make a person say “Dooba Dooba” in your house is intrinsically embarrassing. It’s the type of thing where, if you control somebody’s language, you can control them. And as it unravels, you could say there’s some sinisterness to this innocence — like a word that starts off innocently devolving into something very upsetting and hopefully disturbing.

Q: The movie seems haunted by America’s history — politics, violence, control. How consciously did you weave those ideas into a story that’s essentially about fear inside a home ?

Ehrland Hollingsworth: I mean, one thing — I’m just very interested in American mythology and how that works, and this idea of American exceptionalism in some way, as kind of two sides of the same coin. I think in striving for great things, you can also do bad things. I mean, it’s the whole thing of, like, we’re the same country that had the most serial killers and also went to the moon. Maybe that’s not totally related, but I like to think it is. And I didn’t necessarily use the story of the film as a microcosm of the world — it’s more like it’s not outward-in, but inward-looking-out. So you take this smaller story and look outward to relate it to different things. That’s how I see that working, rather than as any sort of pure metaphor.

Q: You rely almost entirely on home-security footage and handheld digital shots. Was that a creative choice from the start, or did it grow from production constraints ?

Ehrland Hollingsworth: That was the original seed of it. Everything was built around the security cameras. And, I mean, it’s like the production constraint of wanting to make a movie but not having any money.

Q: The house layout feels warped and alive, like a physical extension of madness. How did you and your team design and shoot that environment to make it so disorienting ?

Ehrland Hollingsworth: Well, that’s just the house. That house was creepy. It came with a lot of that, and we did quite a bit of production design — bringing some things in, taking some things out. It was a creepy house. Unfortunately, the house’s suit of armor had been taken away, so that’s not in the film. It’s just a weird place, and it’s got this very strange layout with, like, the milk in the corner. It’s like, oh, well, this is awesome, clearly.

Q: The editing collapses near the end — as if the footage itself is breaking down. What guided you in structuring that descent into visual chaos ?

Ehrland Hollingsworth: That was found more in the editing, when a lot of the interstitials started coming in. The initial ending played out in real time, but it wasn’t really working. So once you have all these other cutaways and stuff, then it’s like, now it should climax into this montage. You can bring in these different elements and crescendo into something. That was found a lot in the editing process — realizing, okay, no, this is how we’re going to process it.

Q: The actors’ performances feel raw and spontaneous, almost improvised. How did you direct them to balance realism with the surreal tension of the story ?

Ehrland Hollingsworth: There wasn’t actually a lot of improv in the film. It was sort of like improv when we had these long scenes — improv to get back to where the script was if you forgot your lines, and adjust lines if you wanted to. I’m not sure there was anything about balancing the two — making something raw and surreal. I think life is pretty surreal sometimes. So, yeah, I think it was just having these more surreal-feeling scenes and letting them play out — that’s what it feels like. It was more about pulling back and letting everything play out than going, okay, how do we make this crazier or something?

Q: The dynamic between Amna and Monroe keeps shifting between empathy and manipulation. Was that emotional tension at the heart of what you wanted to explore ?

Ehrland Hollingsworth: Definitely. I sort of talk about this as a film, to some degree, about toxic vulnerability. It’s the way some people use empathy to make you feel bad for them in a really sadistic way — much like narcissists who make the whole world about them. You can manipulate people’s best intentions, and it’s often the best way to manipulate somebody. Rather than yelling at them or making them feel bad about themselves, you make them feel bad about you. Then you have them — and it’s coming from this place of innocence that you don’t suspect.

Q: The idea of being watched — for safety, but also for control — runs through the whole film. What draws you to that contradiction ?

Ehrland Hollingsworth: I think that’s also the state of the surveillance state, in a sense. Surveillance provides safety, but it’s also a way of control, and it’s harder to object to surveillance because it’s like, “Well, hey, this is what we need to do, even if it makes you uncomfortable.” So you go along with it.

Q: By the end, Dooba Dooba turns from comforting to terrifying. Do you see language itself as unstable or dangerous in the way horror stories use it ?

Ehrland Hollingsworth: I think language is so important, and it has a very magical quality. Magic is passed through language — that’s how people use it. And I think language is always scary to people. That’s an inbuilt human thing. For some reason, saying just a couple of words changes reality in some way.

Q: You refuse to offer closure. Was that a deliberate rejection of narrative comfort, or do you see the film as a kind of ongoing nightmare that never ends ?

Ehrland Hollingsworth: I think both, really. I wanted to have this idea that you never fully get the whole picture of what’s going on. There are still things that are unknown to you, almost unwatchable. That feeling you get from footage where something terrible happens but the camera cuts off before it does — that fascinates me. This isn’t a movie where the camera always turns off before something bad happens, but it removes it just enough. Not showing something can make the world beyond the film feel darker. It’s like we’re willing to show you some messed-up stuff, but there’s even more messed-up stuff that you don’t get to see — stuff that becomes almost sacred to the characters.

Q: Screamfest audiences seemed both disturbed and fascinated. How do you interpret that response — is discomfort the reaction you hope for as a filmmaker ?

Ehrland Hollingsworth: Oh, yeah. I mean, for sure. That’s exactly what you’re going for. You just want people to react to your film, to some degree. But yeah, this film is meant to be disturbing — hopefully not in a gratuitous way.

Q: You worked closely with Joshua Sonny Harris, Michelle Sabella Sligh, and your cast on this project. How collaborative was the creative process behind the camera ?

Ehrland Hollingsworth: I like to think it was very collaborative. It was always about taking ideas from other people, from everyone, and moving it forward. I think they all trusted me to have the right vision and to carry it forward. It was a collaborative experience with everybody.

Q: After a film this haunting and experimental, where do you see your work heading next — deeper into psychological horror, or toward something entirely different ?

Ehrland Hollingsworth: I don’t know. Part of it depends on what people are interested in. I’m interested in many different things. I think it would be fun to do something entirely different — maybe something more in the vein of traditional horror. One thing about experimental films is that you have to extend an arm to the audience and not try to make it purposefully obtuse, although some people could accuse the film of being so. If you go further down the path of dissolving the bounds and rules of filmmaking, at a certain point, it might not cohere fully. I’d love to do more in this space and hone exactly how it goes, but I’d also like to do something entirely different. There’s a biopic I want to do, and there are some more traditional horror films I’d like to try. You always try to bring something fresh to any of them, and having things that feel structurally and rhythmically off would be a lot of fun. So, we’ll see.

Ehrland Hollingsworth is a Los Angeles–based filmmaker known for his experimental approach to horror and narrative structure. Before Dooba Dooba, he worked across short films and multimedia installations that explored perception, identity, and the erosion of memory in the digital age. Ehrland Hollingsworth’s work often refuses traditional storytelling in favor of disorientation and emotional unease, merging analog textures with psychological realism. With Dooba Dooba, he delivers his most audacious and haunting project to date, confirming his reputation as one of the most daring new voices in independent horror cinema.

Dooba Dooba follows a young babysitter, played by Amna Vegha, hired for what should be an ordinary night watching over a fragile teenage girl named Monroe (Betsy Sligh). The family home is covered in security cameras, and the babysitter must repeat the phrase Dooba Dooba as she moves, a bizarre ritual meant to soothe Monroe’s nerves. But as the night unfolds, the surveillance system becomes a window into something far more disturbing. Through a fractured blend of lo-fi visuals, political imagery, and emotional disintegration, Dooba Dooba transforms from a domestic thriller into a hallucinatory meditation on fear, authority, and the loss of meaning. It’s not just a horror film — it’s a lingering nightmare about the illusions of safety and the ghosts that live inside modern control.

Synopsis:

Security cameras installed in the house film a clumsy sixteen-year-old girl terrorizing her well-meaning babysitter.

Dooba Dooba

Written and directed by Ehrland Hollingsworth

Produced by Joshua Sonny Harris, Ehrland Hollingsworth, Michelle Sabella Sligh, Amna Vegha

Starring Betsy Sligh, Amna Vegha, Erin O'Meara, Winston Haynes, Billy Hulsey

Cinematography: David Wright

Production companies: Black Widow Productions, New Hope Studios

Release dates: TBD

Running time: 76 minutes

We sincerely thank writer and director Ehrland Hollingsworth for taking the time to share his insights and answer our questions.