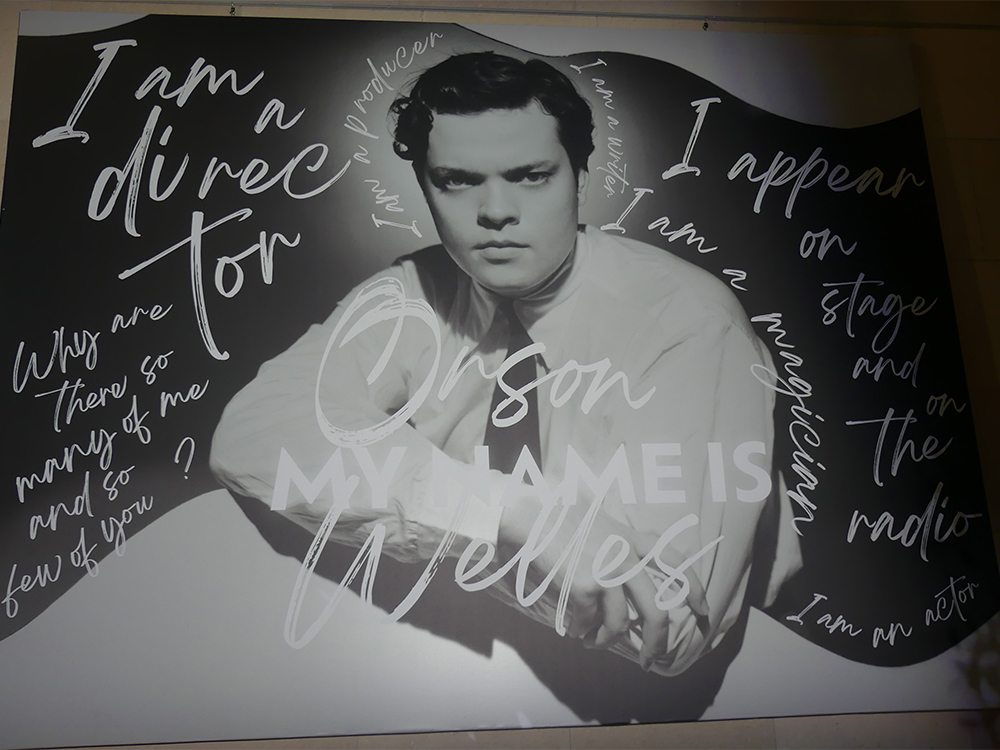

Exhibition - My Name is Orson Welles: a retrospective exploring the mysteries of a cinema giant

By Mulder, Paris, Cinémathèque, 08 october 2025

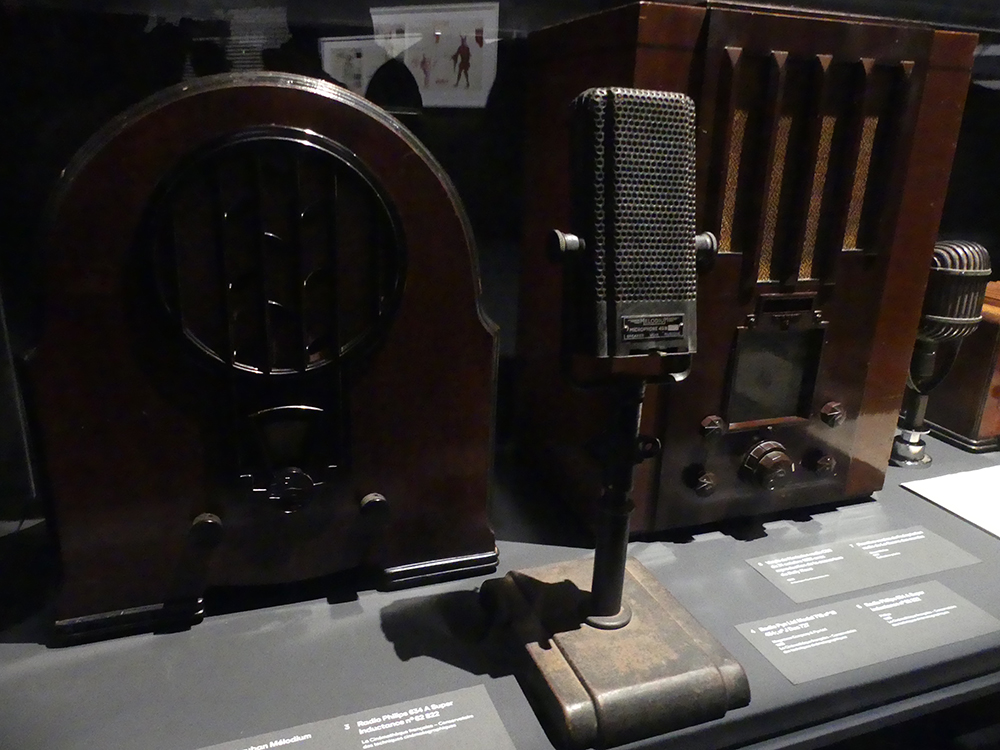

As soon as you step inside the Cinémathèque Française, you enter into an intimate yet monumental conversation with Orson Welles. The exhibition “My Name is Orson Welles” (October 8, 2025 – January 11, 2026) does more than just hang posters and list dates: it maps out a life devoted to exceptionalism, from the young prodigy who preferred Ireland and Spain to a scholarship to Harvard, to the Broadway comet, from the prince of the airwaves who shook America with “The War of the Worlds” to the absolute beginner to whom RKO rolled out an unprecedented red carpet—including final cut—for a debut film that became legendary. At the heart of this journey through more than 400 works lies one obvious conclusion: “exhibiting Welles” means proving, with images and archives, that before and especially after Citizen Kane, the man never stopped reinventing himself, lending his majesty to Carol Reed's The Third Man, inventing a European and independent cinema with Othello, absorbing William Shakespeare, Miguel de Cervantes, Michel de Montaigne, Joseph Conrad, and Karen Blixen until they resonated in an art that thinks with the head and with the hands—sketches, paintings, sculptures: everything exudes the craftsman as much as the visionary.

In the Wellesian maze, the Cinémathèque advances methodically and boldly. Its director, Frédéric Bonnaud, curator of the exhibition, draws on the advice of two specialists, Esteve Riambau and François Thomas, and on the memory of a “third man” who passed away too soon, Jean-Pierre Berthomé. The aim is clear: to “bring order” without freezing the elusive. A double screening room embraces Citizen Kane, a paradoxical film that long dominated the Sight and Sound rankings and which, like Jean-Luc Godard's À bout de souffle, was both a crowning achievement and a vanishing point. Mathieu Macheret reminds us that this “indirect portrait” ushers in a modernity in which Orson Welles invents the “fake”—false identities, false information, pretense—to better confuse myth and reality. Outside the theater, echoes of pop culture (from The Simpsons to The Muppet Show, from Woody Allen to Marcel Gotlib) rub shoulders with artistic rigor: depth of field conceived with Gregg Toland, scores by Bernard Herrmann, architecture of sequence shots that analytical montages expose as evidence of conviction.

But the exhibition refuses to take the heroic shortcut. It recounts the era of wounds, inaugurated with The Magnificent Ambersons and the hellish conflict with the studios; it recalls how RKO, after crowning the “young king,” cut him off from funding for It's All True; it follows his European exile, where Orson Welles acted for Pier Paolo Pasolini, frequented Jean Cocteau, filmed for Jeanne Moreau, and created prototypes that could never be repeated. Here, incompleteness ceases to be a criticism: who ever demanded that Pablo Picasso's paintings be “finished”? Editing, experimenting, inventing forms: this, according to the testimonies gathered by François Thomas and Jean-Pierre Berthomé, is the primary act of a modern artist. Edmond Richard's lighting for The Trial and Falstaff, Alexandre Trauner's precision in connecting Morocco and Italy for Othello, the “multi-table” energy of the editors, the punctuality and high standards noted by Willy Kurant, the frustration of a dream King Lear: these voices compose a “Welles at work” that is the antithesis of the tyrannical cliché.

The biographical novel mirrors political history. Orson Welles, a left-leaning editorialist and emissary for Franklin Delano Roosevelt, ultimately died at the height of Reagan's triumph; the exhibition dares to draw a tempting—and immediately corrected—parallel between Charles Foster Kane and contemporary plutocracies, to better highlight the ambivalence of a figure who paid the price for a freedom deemed insolent. In this respect, the “bear dance” of television sets and commercials, which could be reduced to a decline, becomes a mirror here: the most baroque of filmmakers also knows how to play the game of spectacle, singing with Dean Martin, cutting Rita Hayworth or Marlene Dietrich in half to entertain soldiers, while preserving the absolute integrity of the films. The vortex artist attracts everything—theater, CBS radio's Mercury Theater, television, magic—and twists it to question identity, both that of the world and his own.

The “signature” pieces recount, with an almost sensual attention to detail, how a work becomes a matrix. The giant snow globe faces the “Rosebud” sled; a statuette of King Lear sculpted by Orson Welles himself recalls “thinking with your hands”; portraits by Irving Penn and Cecil Beaton reinscribe the body and face in time; angry letters, born of the 1938 panic hoax based on Herman George Wells (better known as H. G. Wells), replay the power of radio storytelling; storyboards, essays, and unfinished fragments (Don Quixote, The Deep, The Other Side of the Wind) bear witness to this permanent workshop where doubles and potential films are created. Quoted by several filmmakers, Martin Scorsese's injunction— “watch Orson Welles' films, because he alone is cinema”—circulates here as a visiting instruction.

This retrospective gesture does not forget today's viewers or those of tomorrow. Screenings until November 29, lectures, special screenings, rarities from the Filmmuseum München, reissue of interviews with Peter Bogdanovich (Me, Orson Welles, Capricci), a critical biography by Anca Visdei, a catalog from La Table Ronde, and a collection entitled Leur Orson Welles by François Thomas and Jean-Pierre Berthomé: the mediation is in line with the density of the man. The media hail a career that embraces both successes and failures, reveals the driving forces behind a life (from Joseph Cotten, Agnes Moorehead, Everett Sloane, and Paul Stewart to Herbert Yates), and helps a new generation understand why modernity in cinema took such a clear leap forward in 1941. The exhibition, designed on a “human scale,” superimposes chronology and themes to allow everyone to trace their own thread—neophytes, returning visitors, and film buffs alike.

What remains is an intimate shockwave, the impression of having experienced a work that “never lets go.” We come away with the feeling that Citizen Kane didn't just “astound”: it permanently “disrupted” the art of spectacle, as if Orson Welles had chosen to inject doubt into the heart of the system—which, in retrospect, explains both the studios' mistrust and the filmmakers' stubborn loyalty. As we come to the end of the journey, we are reminded of François Truffaut's words: in the world of talking pictures, a single, unmistakable visual temperament stands out immediately, recognizable within three minutes. It bears a name that is now engraved, once again, on the walls of Bercy.

Practical information to extend your immersion: Cinémathèque française, 51 rue de Bercy (Paris 12ᵉ), from October 8, 2025, to January 11, 2026; weekday hours 12 p.m. to 7 p.m. (closed on Tuesdays), weekends and holidays 11 a.m. to 8 p.m., closed on December 25; ticket booking strongly recommended, full price €14, reduced price €11. And if you want to relive the experience on your own terms, you can book a guided tour (Saturdays and Sundays, 4:30 p.m., duration 1.5 hours, ages 8 and up), then slip into a screening—Citizen Kane (1941), The Trial (1962), Othello (1951), Truths and Lies (1973)—to experience, in situ, what the theater still knows how to do: captivate you, as if for the first time, with a film that never ceases to reinvent itself.

Photos : Boris Colletier / Mulderville