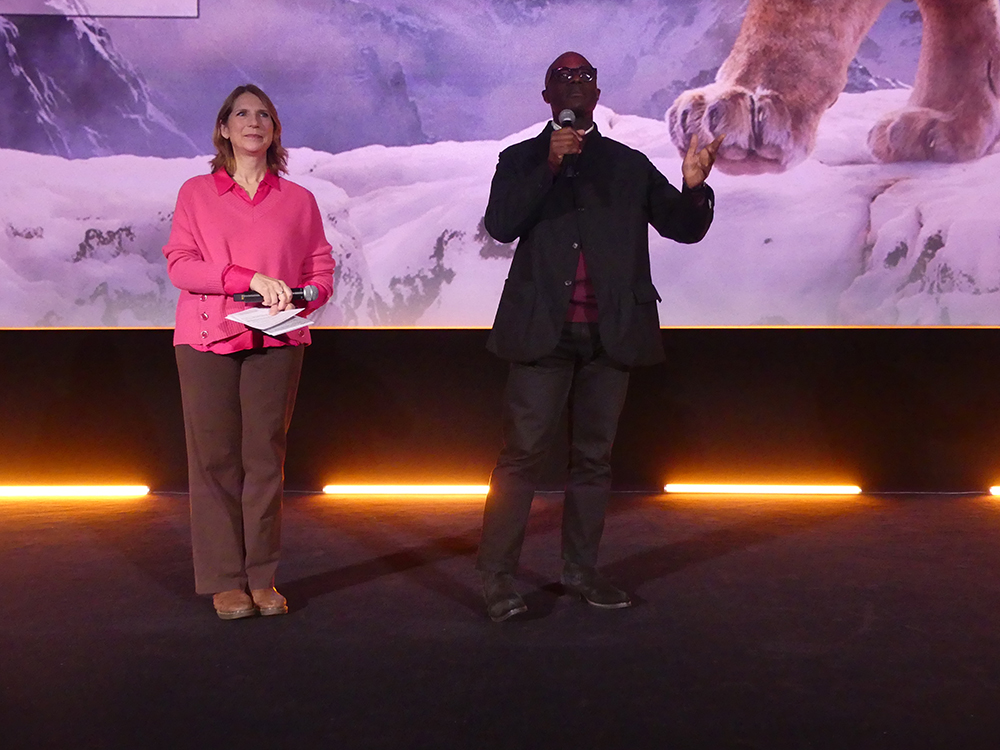

Movies - Mufasa: The Lion King : A special screening with the director Barry Jenkis

By Mulder, Paris, Pathe Beaugrenelle, 13 november 2024

On November 13, 2024, at the Pathé Beaugrenelle in Paris, acclaimed filmmaker Barry Jenkins took center stage to share an exclusive look at Mufasa: The Lion King. During this special event, Barry Jenkins revealed the first forty minutes of his much-anticipated prequel, offering a glimpse into the origins of the legendary lion Mufasa and his complex relationship with his brother, Taka—later known as Scar. The preview not only set the stage for what promises to be an emotional and visually stunning cinematic experience but also underscored the profound themes of family, destiny, and the forces that shape greatness. Following the screening, Barry Jenkins engaged in a candid and insightful discussion, sharing the creative journey behind this ambitious project. From the challenges of directing an entirely digital film to reimagining the characters’ backstories with cultural depth, Barry Jenkins offered a talk in storytelling and innovation. Below, we present the transcription of his talk (no video and photos were allowed), where he delves into the intricate process of bringing the African savannah to life, his inspiration for taking on the project, and the collaboration with a stellar team of artists and animators to craft a timeless tale of legacy and courage.

Q: I believe that the first time you discovered The Lion King you were 14. Tell me about your memories of that time, what you discovered, and what made you want to make this one.

Barry Jenkins: I was a teenager, and I was babysitting my nephews. My sister was a single mom, and when you're watching kids back then, you just put on VHS tapes. So, I just kept putting on different movies, and The Lion King was the one they watched the most. You think they're watching it, and you're watching them, but eventually, you end up watching it with them. In the original Lion King—which is a crazy thing to have happened—there’s this moment where Mufasa dies, and Simba walks up to his father. For many children, it’s the first time they process the idea of losing their parents. Watching my nephews confront those very complex emotions over and over again, but in a very safe way because it's a children's film, was extraordinary. That was one of the elements I remembered when this film came to me. I thought, Oh, there’s something deep in this to be explored.

Q: So, how did you approach that, then, all these years later? I mean, there's so much about this movie that so many of us know and that is deeply ingrained in our cultural history. How did you go about bringing your own vision, your own touch, to this movie ?

Barry Jenkins: Yeah, I think the biggest thing for me, because someone else wrote the script, was that I came on board as the director, and then we workshopped it together. The biggest thing for me is, despite the fact that this is a completely digital movie—we’re not in the savannah with cameras, and there are no actual lions (this is the first film I’ve ever worked on this way)—I still believe the elements of making the film, and a constructivist principle, add up to the aesthetic, the feel of the movie. So, as long as I could have all my key collaborators on the project, I felt like we would end up with something that was very representative of our filmmaking DNA.

Q: This film follows the evolution of the brothers Mufasa and Taka—a brotherhood that gradually turns into a rivalry. For those of us who know the original film, how did you go about creating and fleshing out that backstory? Because it’s difficult—we know what’s coming. How do you go about doing that as a filmmaker ?

Barry Jenkins: It’s just like anything, or like any of the other films I’ve done. You know, for 30 years, people have lived with this idea of Mufasa and Taka. In a very rough way, Taka translates to trash, and Mufasa translates clearly to king in their native tongues. But that was 30 years ago. We got to do this work of going in and really exploring what these names could truly mean. For example, Taka—there’s a saying, I believe in Tanzania: Roto takatou, which means more or less the Holy Spirit. So, in my mind, Taka’s name is Taka because he is Obasi's spirit. (That’s my phone pinging, by the way—I apologize. You guys aren’t being rude; it’s all me. I’m just going to throw that over there somewhere!) And so, we got to really go back and especially look at kids who’ve always had this idea that Taka, or Scar, is the worst person in the world and Mufasa is the best. And that Mufasa is king because great people are kings. I think it’s really wonderful to go back and explore. No—there was a moment in time when Mufasa was just a kid. And with Scar, the idea of nature versus nurture—it’s kind of crazy. Mufasa loses his family and gets adopted into Taka’s family. But the toxic parent, who only knows layers, gets to raise Taka. And the very loving and nurturing parent, Taka’s mom, raises Mufasa. You can see how these two men could grow up to be completely different people. I think it’s a great model for how a lot of us live our lives. Maybe there’s some kid bullying another kid at school every day who looks at this and thinks, Maybe I should treat them a bit nicer because we could grow up to be the president—or friends—or whatever. I don’t know.

Q: It’s really about humanity, in just what we were seeing in these initial images. I’m really looking forward to seeing the rest of the movie—it’s really impressive. As you said before, directing this kind of movie is very different from what you’ve done before. What lessons did you learn in the process of making this movie ?

Barry Jenkins: One: communication. The movie is an hour and 58 minutes, but it’s really an hour and 49 minutes. Then there are 10 minutes of credits because people all over the world worked on this film, and I had to communicate with all of them constantly. Typically, on a film set, I get 200 people, and we’re all standing in the same light. We’re breathing the same air, the camera’s moving, and we’re seeing different things. We’re trying to find the best version of what’s among us to create the art. In this case, I had to communicate those things constantly. So, I learned communication. The technology itself—at the very beginning, we took a 30-second piece of the movie and made that as a test. The scene was set after the big fight with the lions when Ese and Obasi come back. We took 30 seconds of that scene, where Mufasa stands up and Obasi says, I owe you a great debt, Mufasa. I wanted to see what expressions were capable of in this film. We did that 30 seconds at the very beginning to learn every element of the process. Once we did, we tried to disappear the technology and bend the way they make these films to align with how we make our films. So, just learning to communicate and learning to meld this technology—because it’s so very new—so that it could carry our voice in any way we wanted, was the biggest lesson.

Q: Technically, how much were the actors involved in what actually became visually on screen? I mean, how much of their faces and their physicality is actually what we’re seeing ?

Barry Jenkins: None of their faces, none of their physicality. Part of that is because people assume that this movie is made similarly to Avatar or Planet of the Apes. But in those movies, most of the characters walk on two legs, and the actors walk on two legs as well. In this case, the majority of our characters walk on four legs, so you don’t have the same motion capture relationship. We recorded all the voices first. It was almost like directing a live radio play, which was great because, during the pandemic, we had actors all over the world. But they could go into a booth and hear each other simultaneously. It was very seamless. We got all the voices, edited them together, and essentially built the film. We storyboarded it and then used those storyboarded scenes to create a virtual 3D version of the scene. At first, that was very limiting because the animators were working in a way similar to how you would make a Pixar film: you storyboard the whole film, cut it to the voices, and then the animators animate those storyboards. But we were trying to get the storyboards to a point where they could show us what we needed to create so that we could go and shoot it with live virtual cameras. What Disney and MPC (the visual effects studio) did for us as a favor was that I said I wanted the process to be as live as possible. So, the animators themselves—this gets to your question—the animators got into motion capture suits. They figured out a way they could move on two legs that would translate to four legs. It wasn’t that they were recording the actual animation they were going to use. People talk about 2D animation because it’s hand-drawn, and I’ll never forget: in 2005, I was at the San Francisco Film Festival, and a cinematographer named Caroline Champetier—she shot Holy Motors—was there with a film called A Perfect Couple. She described the actress in that film, Valeria Bruni-Tedeschi, as directing with her whole body. And I told the animators, I want you to animate with your whole body. So, they got in the suits. Typically, they would be drawing the movements of the animals, but instead, they were moving with their whole bodies. For example, where Taka and Obasi are having their very last conversation at night—where he says, Deceit is the tool of a great king—it’s hard in animation because it’s so iterative to tell an animator, When he says ‘tool,’ I want his eyes to go down, and when he says ‘great king,’ he should step back and take a breath. It doesn’t feel very warm to have to describe that version after version. But if an animator is live, moving through the scene and hearing the actual principal cast’s voices being played in real time, you can create something that is very subtle but also warm. So, it was the animators’ bodies and the actors’ voices.

Q: And you heading it all up as the director—it’s amazing.

Barry Jenkins: Yeah, it took four years—four years.

Q: My question is about the music. The first movie back in 1994, yes, was very strong with Lebo and music. This time, you worked with Lin-Manuel Miranda. What was the impact on the songs and the musicality of the film ?

Barry Jenkins: Yeah, I mean, the music in The Lion King is very heavy. It kind of, uh—when you take on this job, if there’s pressure, it’s the fact that, you know, I think there’s a joke where he says, And he sang that song for six years straight, and then someone says, Well, who didn’t? Um, that was sort of the thing we had to deal with. But Lebo M is the first song—the first voice you hear. Um, in the screening, like, the very first voice you hear in The Lion King is Lebo. Lin was very adamant about, when he came onto the project, that Lebo needed to be very deeply embedded in the film. I’ve never, never made a musical. Lin-Manuel Miranda has made many musicals, and so it was great to have him on board helping me. and then there are other songs that you hear that are sort of background, that Lebo and Nicholas Britell sort of came up with, um, in these sessions with the South African Gospel Choir at Abbey Road. So there’s just, like, this whole potpourri of, Lin running the songs. I Always Wanted a Brother and Malele—those are, like, really big, like, actual songs. But then the score has all these choral works—the South African Gospel Choir headed by Lebo M, and orchestrated by Nicholas Britell. That is very cool.

Q:. We find the way the animal movement is very realistic, and we are wondering how much you actually worked with actual animals. Did you go to animal sanctuaries? Did you observe real animals to get the realism we see on screen ?

Barry Jenkins: great question. Disney actually does a lot of conservationist work on the continent of Africa, and so they have people, you know, who live amongst these animals at all times—which means they also have a very large research library, you know, of these lions’ movements. Same thing with the animation company MPC. Because they had done the 2019 film, they kind of had a head start on all these different things. And it’s—I’m going to consider that a compliment because one of the things that we always have to be mindful of is that the animals do have to move in the way that they truly can in nature, including the way their muscles operate in their faces. And so, in a way, we’re somewhat limited purely because, as human beings, we don’t see these animals as often as we see human faces. And so we can look at a human face, and with the subtle adjustment of an eye or the setting of a jaw, we can understand what’s being communicated nonverbally. With lions and zebras and other animals, we don’t have that same mental vocabulary—we don’t have that same almost, subconscious vocabulary. And so it’s very tricky to try to figure out how to manipulate those things so that they are readable and discernible by a human audience. Um, but yeah, it’s a lot of research that goes into it. And oftentimes the reason why the animation takes so long is we’re trying to find that balance between getting this right, where the movement is anatomically correct with what these animals can do in the real world, but also still communicative in a cinematic standpoint.

Q: I have a question about the design of the movie. I don’t know if I’m right or wrong, but I have the feeling that this one is less realistic than the first one, where we had the feeling that it was a documentary. Am I right or wrong ? Did you change the design ?

Barry Jenkins: I didn’t work on the last film, so I can’t change—do you mean the 2019? I didn’t work on that film, so I can’t say. Um, and I also can’t say what’s real or what’s not real, or what’s documentary or not documentary. I think we were going for, um, a language that was very understandable in a non-verbal way by the audience. So if that’s a little bit different than realism, um, I think that’s fine. But I don’t know that that film looked very real, either. I mean, they’re all digital, animation. But it wasn’t intentional.

Q: One thing that is interesting is there is a throwback to some of the same actors, um, from that movie that are in this movie as well.

Barry Jenkins: Well, there’s a couple, but, so many, uh, new voices—uh, new, new faces.

Q: Hello, I’m Shana from Just Focus, and, I was wondering that we finally see Kiara, one of the main characters of, The Lion King 2. And, how does The Lion King 2 help you build this? uh, this movie? And, will we see maybe the bond between Simba and Kiara, or maybe even Kovu in this movie—without a spoiler, of course ?

Barry Jenkins: Yeah, I can’t answer any of those questions. Um, I have seen The Lion King 2, um, but I’m also not allowed to say whether this is inspired by, or based on, or even in relation to The Lion King 2. there are some hardcore Lion King fans, I learned very quickly, and they know way more about these characters than I did when I started this project. but Kiara is awesome, and she is sort of, like, the emotional core of this film. I have no comments on those other characters.

Q: I know you didn’t work on the initial movies—but how much did you actually go back to them and look at them again to work on this character development between characters like Timon and Pumbaa, for example ?

Barry Jenkins: Yeah, I looked at the 1994 film and the Broadway musical. Those are my two favorite versions of The Lion King, especially the Broadway show by Julie Taymor. I really love that one in particular because it really situates The Lion King on the continent of Africa.

You can discover our photos in our Flickr page

Synopis :

Mufasa: The Lion King will take the form of flashbacks. Rafiki, Timon and Pumbaa will tell a young lion cub the story and rise of one of the greatest kings that the Land of Lions has ever borne.

Mufasa: The Lion King

Directed by Barry Jenkins

Written by Jeff Nathanson

Based on Disney's The Lion King by Irene Mecchi, Jonathan Roberts, Linda Woolverton

Produced by Adele Romanski, Mark Ceryak

Starring Aaron Pierre, Kelvin Harrison Jr, John Kani, Seth Rogen, Billy Eichner, Tiffany Boone, Donald Glover, Mads Mikkelsen, Thandiwe Newton, Lennie James, Blue Ivy Carter, Beyoncé Knowles-Carter

Cinematography : James Laxton

Edited by Joi McMillon

Music by Hans Zimmer, Pharrell Williams, Lin-Manuel Miranda, Nicholas Britell, Mark Mancina

Production companies: Walt Disney Pictures, Pastel Productions

Distributed by Walt Disney Studios Motion Pictures

Release date : December 18, 2024 (France), December 20, 2024 (United States

Photos : Boris Colletier / Mulderville