Festivals - FCAD 2020 : The Last Hillbilly - Our Thomas Jenkoe and Diane-Sara Bouzgarrou' interview

By Mulder, Deauville, 09 september 2020

Q: Hello Diane and Thomas, The Last Hillbilly is the portrait of a family through the words of one of them, a surprising witness to a world that is disappearing and of which he is the poet. Can you tell us about the genesis of this project and the 7 years you spent on it?

Thomas Jenkoe and Diane-Sara Bouzgarrou : We had the intuition very early on that Brian was a real cinematic character thanks to his psychological density and the precision of his thinking about the universe around him. It was he who came to us while we were in Kentucky in 2013. We wanted to spend time in a place that would not be mapped by tourism, so that is where we met him. He comes to talk to us, curious to see two French people in this region. It must be said that eastern Kentucky is a territory apart, as we have discovered, where the social organization is woven around family clans. A rural, remote area, located in the foothills of the Appalachian Mountains, this region has always maintained a special relationship with the rest of the United States, cultivating a spirit of independence and a strong desire for self-sufficiency, inherited from the first settlers. And the rest of America does them well, as the people who live there are known as "hillbillies". We were therefore surprised and interested when it appeared to us that Brian was seizing on this insult to take it to his advantage and question the stereotypes it conveys, in order to draw his identity. That's when we decided to create a cinematographic work around and with him and to invite the spectator to share the experience we had: to inhabit his inner world and to walk through his universe in his steps for the time of a film. For seven years, we regularly visited his home, in his mobile home in the middle of the hills. He introduced us to his family and then to his loved ones. We also got involved in the daily life on the spot because we felt it was important to participate in order to feel truly legitimate. When we returned to France, we kept in touch thanks to emails and Skype. That's how, beyond the film, a friendly relationship was created.

Q : Can you tell us about your filming, more precisely about the locations in Kentucky where you shot this film ?

Diane-Sara Bouzgarrou: Eastern Kentucky is characterized by a rugged geography where travel by car is complicated because of old roads - when there are any! Sometimes it's just a simple passage that winds its way up the hillside. For example, if the Ritchie's all live on the same side of the hill, it is unthinkable to be able to get to each other's homes without a 4x4. In winter, with frost and snow, it becomes particularly dangerous. You feel like you're really cut off from the world. This impression is prolonged in the beautiful season because the population density is low. Nature has kept this wilderness and sublime aspect, yet it also bears the scars of the mining industry: the water is polluted and part of the hilltops have been blown up with dynamite to extract coal. It is therefore a paradoxical landscape that we discovered and that we tried to capture during the shooting.

Q: What can you tell us about your collaboration with Brian Ritchie ?

Thomas Jenkoe and Diane-Sara Bouzgarrou : We lived for many weeks, sometimes a month or two in the intimacy of Brian's home during those 7 years. We lived in his mobile home with him, his dogs, his children. From this extreme intimacy was born a total and mutual trust. Brian is modest but for all that, he was happy that we were making this film, happy to play the game. Sometimes we filmed spontaneous situations, sometimes we had an impact on reality, we decided together that the moment we lived was worth working on through our cinema. This scene where Brian addresses the camera to tell us about the hillbillies is the conclusion of an evening where we talked at length, where we were even in conflict. At the end of our discussion, we felt it was essential to give an account of what had animated us. So we said to Brian, "This is your moment, seize it, address the camera, go for it! ». And he did so, because he shared the same feeling as we did about the need to tell the paradoxes of his region.

Q: How did the texts written by Brian come to be heard ?

Thomas Jenkoe and Diane-Sara Bouzgarrou: These texts are an essential element in the construction of the film. We gave him a digital recorder very early on so that he could, alone, record the very spontaneous traces of his inner life. This is how this long text was born, shouted, like a preach, at the beginning of the film. Brian was inhabited by the work we were doing, and very active in its creation. He wrote and performed this text on his own and then offered it to us, leaving us free to use it as we wished. We also sometimes asked him to write certain passages, such as the poem about the death of the deer, which serves as a prologue. Everything was done this way, in a great fluidity, with great confidence and united by a shared pleasure to go to the end of our common cinematographic gesture.

Q: After the video in small size at the beginning of your documentary film you then switch to a 1.33 format. Can you explain the reasons for these two formats ?

Thomas Jenkoe and Diane-Sara Bouzgarrou: We thought, from the genesis of the project, to work on the idea of decomposing a space. To do this, we chose to use a narrow frame, hence the use of the almost square or 1.33 format. This somewhat hieratic format makes it possible to immediately break the stereotypical representations of the cinema of large spaces and not to give in to the excessiveness they seem to call for. If our film has a link with the western, the myth persists in a minimalist and twilight form - and not in such an iconic, visual and spectacular form that it prevents us from seeing the rest, namely the human and the concrete relationship to nature. Conversely, the 1:33 format translates a necessarily concentrated point of view. We wanted to stay as close as possible to the people who make these great spaces and experience them. As for the smartphone format, it opens and closes the film. It allows you to be in a very raw, raw image, as if taken on the fly, and thus render the violence and beauty of reality. These snapshots then seem to be torn from Brian's mind, like so many shreds of memory. This format introduces a distance from what is played out in the image - the death of the deer and this mysterious epidemic, used as a metaphor in our film, and the final scene with these two children's characters disappearing in the dark, beyond even the black of their night, the black of the cinema screen that sucks them in. The darkness in which they disappear with the fragile "Help me" sound.

Q : According to you, what are the ingredients of a good documentary ?

Thomas Jenkoe and Diane-Sara Bouzgarrou: There are no magic ingredients! The term "documentary" encompasses a dizzying reality and diversity of approaches. Filmmakers who embark on this path tend more and more to push back the limits of what working with reality can mean. It is therefore difficult to give a good "recipe", and fortunately. Like any work, documentary film rises up when it brings into play a point of view that renews the view we can take as human beings and spectators on what we call "the real". Not all documentaries are devoted to bringing characters into play, but for The Last Hillbilly, this was the case, so we will rather evoke the documentary "incarnate". For this kind of film, it is essential to create with strong, complex, dense characters, as much in what they physically exude as in what they manage to show in terms of situations that involve them, and to articulate at the heart of their speech, whatever its modality, moreover. However, there are some excellent documentaries that do not rely on having a good story or good characters. This is what makes the beauty of this practice of real cinema: the immense artistic freedom it allows. The real is not limited to what we see and hear, the real is also all the possibilities it encompasses, memories, fantasies, projections. To be able to give life to these possibilities of the real, to go beyond the life that one seizes on the fly to explore less obvious paths, is also what makes the beauty of a cinema documentary. Then, what is most important is the sincere and demanding relationship to the raw material that the filmed reality represents. An aesthetic and artistic commitment, ethics, daring, and a constant demand at every stage of the film's creation, this is what drives us when we make a film. All in all, what makes a film take off is the commitment of the director and all his collaborators to a common vision.

Q : What were the main difficulties encountered during the making of this film ?

Thomas Jenkoe and Diane-Sara Bouzgarrou : It was not easy to take on the role of filmmaker and cinematographer and sound engineer at the same time. Yet we absolutely do not regret this choice. It represented a greater mental and work load on location but we could not have made the film in any other way, not this one. The strength of the film is also the intimacy we feel between us filmmakers and the characters in the film. It also took time to conquer certain scenes because we gradually tamed some of the characters in the film, at first shy and modest. We lived with them, within the family, so sometimes we had to move away from this status to find our place as filmmakers. We were very attentive and concerned about filming with respect for the people we met, while at the same time making people understand what was at stake in the film, in filming, in being filmed. It took time and it's quite normal, everyone who creates a documentary faces this challenge.

Q: Can you tell us about your editing, which plays an important part in the successful immersion of this documentary film ?

Thomas Jenkoe and Diane-Sara Bouzgarrou: Théophile Gay-Mazas was a decisive collaborator on this film indeed. For four months, we worked hard to produce a film that was strong in its aesthetic and narrative biases as well as in its content. We wanted to offer the viewer a sensitive experience and the editing was a very important phase in the creation of the film. We built it by making it oscillate between dives into the flow of consciousness and Brian's poetic texts and an immersion in the narrative situations of Ritchie's daily life. It was like any editing experience, a moment when the work becomes almost musical. It's all about finding the right rhythm, being extremely precise, meticulous, finding after several years of shooting what was going to structure the film, going through the different moments of the shooting, the different temporalities, the advance of time, the children growing up. Brian was obviously the protagonist and the motor of the action. Our work was extremely precise, especially during the sequences which are based on an associative editing which are like a dive into Brian's interiority. The music also played a very important role in the way we structured the film and how we wanted to capture the reality we were filming. With Théophile, we wanted to create a short, dense film. We disrupted everything, then spent a lot of time talking, creating the structure, clarifying the story we wanted to tell, finding the key to the film among all those hours of rushes. We quickly grasped the beauty, the humor, the cruelty, the strength of the scenes embodied by the children of the Ritchie clan. Brian is the hero, but the film progresses towards a relay passage given to the children. It is they who carry the narration in the last third of the film. Their vital momentum goes beyond the adult world and it is with them that the film ends. We also quickly chose to open with the prologue narrating an epidemic and we knew that the preaching that Brian proposes just after this prologue was fundamental. For this text, we didn't have an image, but its power was such that we had to invent it, find a way to make this long cry of despair that runs through American history resonate, to get to him, to Brian, and transform this performance into a moment of cinema.

Q: Your film is divided into three parts, Under the Family tree, The Wasteland and Land of Tomorrow. Can you tell us about this division?

Thomas Jenkoe and Diane-Sara Bouzgarrou: Even more than cinematographic references, literary influences have irrigated our creative research and the choice of chaptering the film partly stems from this. We shot over several years and we wanted the film to bear witness to the passage of time, to see children grow up, to create a fresco where time stretches without the viewer perceiving it precisely. Thus the story is punctuated by chapters. The prologue speaks of a mysterious epidemic that decimated deer in the Appalachians. It is a powerful allegory of death at work in this region and announces the narrative project of the film. The first part - under a family tree - deals with the importance of the clan, which is under threat from a deaf woman. What happens outside, in the hills and elsewhere, contaminates the inside of the family unit. The second part - the wasteland - deals with the fate of those, like Brian, who have remained in this region, who endure its harshness, who see it declining and yet continue to cling to their way of life. The third part - the land of tomorrow - is based on a slow shift in perspective. Brian is more and more devoured by loneliness and finds himself at a loss for words. The children, previously present in the background, become competing characters. They impose themselves by their candor and their impulse for life which contrasts with Brian's isolation and despair.

Q: Can you tell us how you divided up the making of this documentary film ?

Thomas Jenkoe and Diane-Sara Bouzgarrou: We are both co-directors and, from writing to the final stages of post-production of the film, we worked hand in hand, as a duo. Sometimes one had an intuition, an inspiration, a flash of lightning, and the other welcomed it, bounced back, it was all very fluid. We are used to working together, Thomas on Diane's films, Diane on his, officially, or behind the scenes. Thomas did the image, and Diane did the sound. On location, Diane had more freedom to talk to the filmed people, to guide them during the filmed scenes, Thomas had the responsibility to bring our common gaze on the filmed situations. It happened that Diane suddenly felt a scene unfold and took her camera to shoot in her turn. Thomas sometimes took sounds. And our duo has always been able to find very important bounces in the person of our producer Jean-Laurent Csinidis, as Théophile Gay-Mazas, as with the other collaborators we worked with in post-production.

Q : In the current context of the coronavirus, as a filmmaker, can you tell us about the many difficulties involved ?

Thomas Jenkoe and Diane-Sara Bouzgarrou: The situation is very complex, and we are concerned. We were fortunate to have finished shooting and editing our film before the containment. However, we had to learn how to work on sound editing remotely, via video applications, and Pierre Armand (sound editing & mixing) put a lot of effort into keeping the work moving forward. We adapted and fortunately we were able to finish the mixing and calibration in person this summer. But the situation is worrying, we were shocked to see that in France, politicians have ignored for long weeks the impasse in which the people who create and bring art in all its forms to life have found themselves. It is nowadays extremely complicated to create, to continue to create. But we must fight, and we must make ourselves heard. We are worried but also united in the face of the ordeal with all those who fight so that films, plays, concerts, exhibitions, continue to exist.

Q : Your film is presented as part of the American Film Festival. How does it feel to see your film selected in this international festival ?

Thomas Jenkoe and Diane-Sara Bouzgarrou: It's a great honor and an immense joy! Deauville is a very important festival of international scope. It's also a generalist festival: if it's always very interesting to be in documentary festivals, it's important, to acquire true legitimacy, to be selected in festivals that mix fiction and documentary. When you feel that the film is understood as a cinema film, whatever the genre it belongs to. It was all the more pleasant to be selected at Deauville in this context, we are extremely happy and grateful to all the festivals that fought to take place, and happy to have the chance to finally show the film. Being here in Deauville is a unique experience for us. It's a great pleasure to be back in theaters, in festivals, and especially at this festival, which is a festival dedicated to America, it's a real recognition of our work.

Q: Who are your favorite directors and which films are the main drivers of your artistic creation ?

Thomas Jenkoe and Diane-Sara Bouzgarrou: It's always tricky to answer this question because we don't have a favorite film, or a favorite filmmaker, it's too little and our tastes sometimes take us from one spectrum of filmmaking to another. Cronenberg, Ferrara, Cassavetes, Herzog, the work of Kelly Reichardt, Terrence Mallick, John Carpenter, Jean-Daniel Pollet, Dennis Hopper's Out of the blue, Pasolini's La rabbia... It's difficult to name just a few names, a few film titles, especially since it varies according to the periods of our respective lives. In any case, we both have a passion for giving an account of a character's interiority, whether real or invented or even fantasized. Entering into the intimacy of the mental, daily, geographical universe of a human being and being able to create and propose a cinematographic experience to the spectator from there is a real driving force for both of us. The form is also very important. Inventiveness and the aesthetic project cannot be put on the back burner. What moves us is to take risks, to go to the end of a gesture while remaining in something extremely sincere and accessible, which detaches itself from the intellect. A film is received as much by the body as by the mind. The body and the sensations, the emotions count more than the concept, the theory.

Q : What new project are you currently working on ?

Thomas Jenkoe: Diane has been working in parallel on writing a film documentary for some time. We also have a strong desire to work together again and we already have a project that is emerging and taking shape within us. The desire is there, but we will of course have to adapt to the evolution of the health crisis. As the project is a second American component, we hope to be able to start scouting as soon as possible.

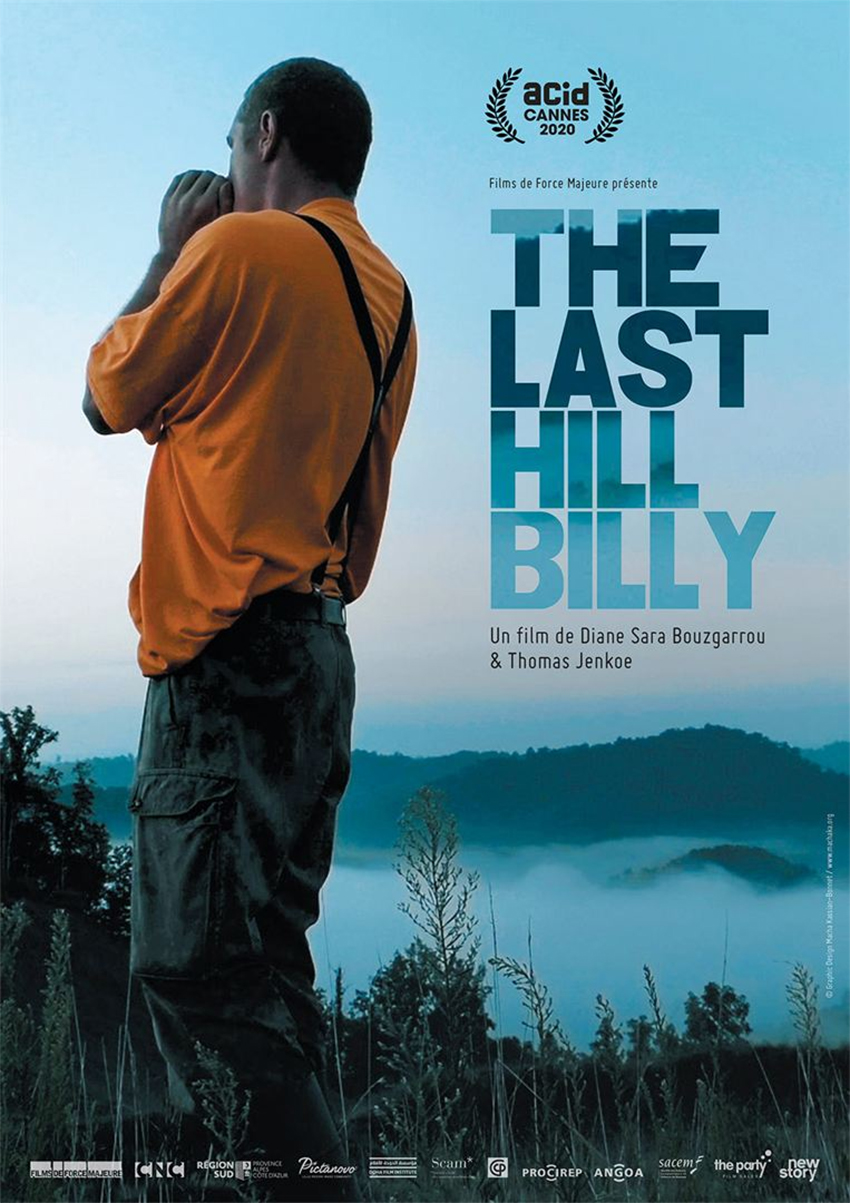

Synopsis :

In the Appalachian Mountains, Eastern Kentucky, people feel less American than Appalachian. These rural white Americans lived through the economic decline of their region. In the United States, they are called "hillbillies": hillbillies, hillbillies of the hills. The Last Hillbilly is the portrait of a family through the words of one of them, a surprising witness of a world that is disappearing and of which he is the poet.

The Last Hillbilly

A film written and directed by Thomas Jenkoe and Diane-Sara Bouzgarrou

Composer : Jay Gambitt

Director of photography : Thomas Jenkoe

Editing: Théophile Gay-Mazas

Sound engineer: Diane-Sara Bouzgarrou

Mixing : Pierre Armand

Sound editor : Pierre Armand

Production: Force Majeure Film

Distributor: New Story (France)

Release date: December 2020 (France)

Runnint time : 80mns

We would like to thank Thomas Jenkoe and Diane-Sara Bouzgarrou for answering our questions, and also Claire Viroulaud for her assistance.